#MovieFailMondays: Star Trek Into Darkness

Every week we bring you a new movie that contains a logical fallacy you’ll find on the LSAT. Who says Netflix can’t help you study?

People didn’t know what to expect when J.J. Abrams was picked to helm the reboot of the Star Trek franchise in 2009. Would it be the gritty reboot of Batman? The campy reboot of Footloose? The angsty reboot of The Incredible Hulk? The Norton-y reboot of The Incredible Hulk?

Instead, we got an action-filled, heartfelt, somewhat confusing reboot of a beloved franchise. The movie made nearly $400 million dollars, and a sequel was all but assured. Four years later, we were treated to the second film in the series: Star Trek Into Darkness.

As is traditional in the sci-fi world (thanks, Empire), the sequel sees the crew of the Enterprise split up because of demotion (Kirk), reassignment (Spock), and arguments over weapons of mass destruction (Colin PowellScotty).

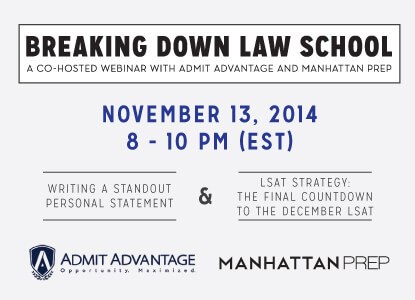

Breaking Down Law School Admissions with Manhattan LSAT and Admit Advantage

Are You Prepared for Law School Admissions?

Join Manhattan LSAT and Admit Advantage for a free online workshop to help you put together a successful law school application.

This workshop will discuss how right personal statement can make all the difference in your law school applications. Even applicants with great LSAT scores and a high GPA need top-notch personal statements to set them apart from the pack. Admit Advantage’s Director of Law Admissions will teach you how to make the best impression with your personal statement.

Are you also getting ready to sit for the December 2014 LSAT? Veteran Manhattan LSAT instructor, Brian Birdwell, will focus on what kind of prep to do in the last weeks leading up to the test. One of the key points here is to be prepared to adapt to little twists that you didn’t expect. Brian will teach you a hard LSAT game where that’s important. Detailed Q&A to follow.

Breaking Down Law School: Writing a Standout Personal Statement & Strategy for the December LSAT

Thursday, November 13 (8:00 – 10:00 PM EDT)

Sign Up Here

Mary Adkins: Let’s LSAT Excerpt

Below is an excerpt from Let’s LSAT: 180 Tips from 180 Students on how to Score 180 on your LSAT, which includes an interview with one of our LSAT instructors, Mary Adkins. Mary has degrees from Yale Law School and Duke, and has over 8 years of experience teaching the LSAT after scoring in the 99th percentile on the test.

Below is an excerpt from Let’s LSAT: 180 Tips from 180 Students on how to Score 180 on your LSAT, which includes an interview with one of our LSAT instructors, Mary Adkins. Mary has degrees from Yale Law School and Duke, and has over 8 years of experience teaching the LSAT after scoring in the 99th percentile on the test.

Jacob: What should one’s goals be when studying for the LSAT?

Mary: I think a misconception that people often have is that they can improve their LSAT score by learning tricks, and the reason I think that’s so dangerous is it’s only going to get you so far. I mean, there are certain patterns to the test and we can teach those patterns. People can learn what to look for and how to spot an extreme term and a wrong answer choice, but unless you really understand the underlying skills that the test is designed to evaluate, your score isn’t going to be in the top percentile.

So, I’d say the goal should not be learning tricks, but learning what the test is designed to test: your ability to think logically. The goal should be to come up to that threshold and become a more logical, attuned, precise thinker. That’s the best thing you can do to be better at the LSAT, but the beauty of this is that it’s not just going to make you better at the LSAT – it’s going to make you a better logical thinker overall, which will make you a better student and a better lawyer.

Jacob: So, if your goal is to become a more logical thinker, it’ll show in your LSAT score, will it not?

Mary: I believe it would. I was just going to say, as a tutor and teacher, of course I’m very excited when my students reach their goal scores or when my students see a lot of improvement, but one of my most rewarding moments, as a teacher, was when one of my students, at the end of the course, told me that he felt smarter having taken it. That’s exactly what we’re going for. It’s like an overall improvement in thinking ability. One way that’s manifested is in the LSAT, but it’s not exclusive to the LSAT.

Jacob: How long would you recommend studying for, as far as being able to change your thinking?

Mary: It’s so specific to the person, so it’s really hard to say, to be honest. I think several months, at least. To be safe, you should give yourself several months. I wanted to bring this up at some point, actually, because my colleague, Matt Sherman, has a brilliant response to the idea that you can peak too soon when it comes to the LSAT – he thinks it’s a myth.

There is no peaking too soon: you only get better at the LSAT the longer you study it. You don’t get worse. So, starting as far in advance as possible, in that view, would be beneficial. I mean, life’s realities make that impossible for most of us. We’re not going to study the LSAT for years, but if we did, we would be better at it when we finally took it. So, several months is kind of the general answer that I would give to that question, but even students starting to study two or three months in advance find that they’re really under a lot of pressure. They’re trying to do too much in a really short amount of time.

So, even 3-4 months in advance is still putting a lot of pressure on yourself, particularly if you have other obligations, like work or school, but I find students tend to find six months in advance much more manageable. Again, six months is not always long enough for them to see as much improvement as they want. So, that’s when it really becomes person-specific.

Studying for the LSAT? Manhattan Prep offers a free LSAT practice exam, and free Manhattan LSAT preview classes running all the time near you, or online. Be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+, LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter!

Advanced Negation Techniques: Part II of III, A Do and a Don’t for Extreme Statements

I LOVE Beyoncé. I want to sing like her and be like her, and last month I was supposed to fly to Dallas just to go to her concert with my sister. But instead, my flight was canceled and I was stranded in Queens watching You Tube clips while my sister and brother-in-law tried repeatedly to Facetime me from the rafters of the enormous theater. My self-pity video marathon included “All the Single Ladies,” and later, when I was thinking about this series and how best to describe negation technique, I thought of the song. While putting a ring on it is what Beyoncé wants for all you single ladies, what I want for you is this: When you’re facing an extreme statement (“all” “none” “best” “worst”)—not unlike my adoration for Queen B, herself—what I want you to do is put a hole in it.

I LOVE Beyoncé. I want to sing like her and be like her, and last month I was supposed to fly to Dallas just to go to her concert with my sister. But instead, my flight was canceled and I was stranded in Queens watching You Tube clips while my sister and brother-in-law tried repeatedly to Facetime me from the rafters of the enormous theater. My self-pity video marathon included “All the Single Ladies,” and later, when I was thinking about this series and how best to describe negation technique, I thought of the song. While putting a ring on it is what Beyoncé wants for all you single ladies, what I want for you is this: When you’re facing an extreme statement (“all” “none” “best” “worst”)—not unlike my adoration for Queen B, herself—what I want you to do is put a hole in it.

For a quick refresher, we’re discussing how to “negate” an answer choice to a necessary assumption question on the logical reasoning section of the LSAT. You do this in order to test it. If negating the answer choice makes the argument fall apart, it is necessary. (If negating the answer choice doesn’t destroy the argument, or if you can’t tell what it does, look for a better answer.) Last week I wrote my first post of three on negation techniques. Today, we keep going.

What do I mean by “put a hole in it?”

If the answer choice reads, “All birds fly,” you negate it by poking a hole in it: not all birds fly. Or some birds don’t fly. Same thing. Either way, notice what we’re doing. If the statement were a big hot air balloon, we’d be pin-pricking it. We aren’t, in other words, trying to melt it down then mold it into something else completely: “No birds fly.” That’s not negation. That brings me to the DON’T of this post, what my friend calls roofing it.

Roofing a joke is when people are discussing a subject and someone takes it too far. A classic example is when someone calls you Hitler when you express your view that a local park needs a thorough mowing. Or when everyone is discussing how annoying skunks are, and someone suggests we just blow up all the skunks.

When it comes to extreme answer choices to necessary assumption questions, don’t negate the sweeping statement with an opposing sweeping statement—don’t roof it.

Suppose (A) reads, “Dr. Seuss is the best children’s author ever.” You could negate this by saying, “There was another children’s author who was as good as Dr. Seuss.” You wouldn’t say, “Dr. Seuss was the worst children’s author ever to walk on earth.” That would be roofing it.

Say (B) reads, “Dr. Seuss wrote faster than any other writer in history.” Negate it: He didn’t. Or, someone wrote faster than him. Yes, and yes. Roofing it: He wrote as slow as your granny backing out of her driveway. Too far.

In sum, when it comes to extreme statements in answer choices, poke it, don’t roof it.

Next week we’ll be discussing my rule for negating mild statements, courtesy of Destiny’s Child.

Read Advanced Negation Techniques: Part I of III.

Mary’s LSAT Morning-Of Cheat Sheet

You aren’t allowed to take into the LSAT a cheat sheet of key rules, but what if you were? I made one for you.

You aren’t allowed to take into the LSAT a cheat sheet of key rules, but what if you were? I made one for you.

Don’t sneak it in (not that you could—my bike map was confiscated), but maybe give it a read the morning of, or print out a copy to review at stoplights on the way there.

Better yet, use the idea as inspiration to make your own. Remember when as a kid you’d be assigned flashcards, and you thought the point was the set of cards, itself, when really it was making the cards that taught you the material (clever teachers!)? Creating your own one-pager can be a great study tool during the final few days before the test.

Here’s mine:

1. On matching questions, principle questions, and assumption family questions, be sure to characterize the conclusion of the argument you’re trying to match, find a principle to support, or analyze. I boil conclusion characterization down to two categories: room for doubt, and no room for doubt. “Room for doubt” conclusions rely on terms like: may, could, likely, probably, possibly. “No room for doubt” conclusions rely on stronger language: will, must, should, is, does. The right answer choice will respond correctly to the type of conclusion you’re dealing with.

2. On weaken and strengthen questions, be suspicious of terms in the answer choice that make it vague: some, sometimes, often, many. (Because remember, “many” just means “some,” and “some” just means “more than one.”) Also be wary of any answer choice that could “go either way”—that in one interpretation strengthens, but in another arguably valid interpretation, could weaken.

3. Only, the only, and only if. Only dogs bark = It barks only if it’s a dog = The only thing that barks is a dog = If it barks, it’s a dog. All are diagrammed: B –> D

4. Unless is “if not.” Don’t go unless I tell you to = If I don’t tell you to, don’t go, i.e. ~Tell you –> ~Go

Read more

Why (and How) LSAT Reading Comprehension Can Be Improved Part III

This is part 3 of Mary Adkins’ series on improving LSAT Reading Comprehension ability. You can check out part 1 here: Why (and How) LSAT Reading Comprehension Can Be Improved and part 2 here: LSAT Reading Comp Is a Bad Play: Advice for Sub-text Sleuths

Watch Out for Reading Comp Red Herrings

When you start a reading comp passage, you’re reading for the central argument, or what our curriculum/books like to call “the scale.” On easier passages, the two sides are laid out for you immediately. For example, in the Reader Response Theory passage—PrepTest 43, Passage 3—the two sides of the argument (RR Theory on one hand and Formalism on the other) are given to us in the first paragraph. As a result, few students in our courses have trouble identifying the two sides of the scale.

In more difficult passages, however, the central issue doesn’t appear until later—maybe at the end of the first paragraph, or even in the second. In PrepTest 27, Passage 1 on jury impartiality, for example, the real issue doesn’t come up until the end of the last paragraph.

How do you figure out, then, what is truly the central issue? Here are two tips—one “Don’t,” and one “Do.”

DON’T Marry the First Dichotomy That Walks in the Door

If you’re presented with two conflicting views in the first sentence, odds are that they’re the two sides of the argument, but they might not be. If they passage changes direction and starts discussing something else, you need to be able to adjust.

The key is to be flexible. Don’t assume that whatever central argument you spot in the first sentence or paragraph is absolutely what the passage is about.

DO Follow the Author

So how to be sure? Follow the author’s voice. Whatever the scale, the author is going to have an opinion about it—you will be able to place him or her on one side or the other. (One exception: passages that are just informative, but these are rare.)

In the PrepTest 27 passage I mentioned above, the one about jury impartiality, the way to identify the true scale (which again, appears at the very end of the passage) is to realize that’s where the author gives us a solid opinion. Because the opinion isn’t what we expect, we have to shift our scale.

Only when you have a full picture of how the author views what he/she is discussing can you feel confident that the central argument you’ve identified is correct.

Three Things You Should Do to Prepare for LSAT Test Day (And One Thing You Absolutely Should Not)

By Evyn Williams

Everyone knows that test day will inevitably be a stressful and hectic event, but you can minimize the madness by being prepared for even the strangest of LSAT happenings.

My own LSAT test day experience was rife with peril, but I made it through, and so can you. Here are three things you should do to get ready for the big day (and one you really shouldn’t):

1. DO read the LSAT test day rules.Then re-read them. Then re-read them again. Then commit them to memory as though they are the Gettysburg Address and you are Lincoln and the fate of the country literally depends on you knowing this thing word for word.

Read more

Beat the Heat: Tips for Staying Focused All Summer Long

“It’s summertime, and the livin’ is easy.” This blissful lyric may ring true for some lucky folk, but for anyone gearing up for the October LSATand working tobalance a summer internship, a weekend job, and a social life, the summertime can be an extremely overwhelming and stressful time of year. As much as we love to embrace the warm weather, the shining sun, and the weekend festivities, it is undeniable that these distractions only dampen our focus and motivation to hit the books and master those daunting logic games.

What is also undeniable is the fact that the October LSAT is less than three months away, which means that it’s time to toss the excuses and start cracking down. To get you on track, we have compiled some useful tips to help you stay focused through the summer and up until test day.

Start Early: Personal trainers often tell their clients to hit the gym first thing in the morning so that there are no excuses to blow off working out later in the day. Take this advice and apply it to your studies. If you know that your energy dips in the afternoon or evening or that your group of friends likes to get together at night, schedule your study time early in the day.

Read more

Ye Olde’ Last Minute LSAT Tips for the June LSAT

If you’re having a bit of an LSAT freak-out, take a break from your umpteenth preptest, stop negating assumptions and talking about contrapositives. Drink some tea (not Long Island), and read some tips:

Final tips from people other than your mother

Tips for chilling out and getting YOUR best score

What to do the night before the LSAT

LSAT Weaken Questions – Logical Reasoning

Weaken questions can operate in a few different ways. Let’s look at some examples.

Sep 09 Exam, Section 4, #2

Here’s the basic logic given in the argument:

You can always keep your hands warm by putting on extra layers of clothing (clothing that keeps the vital organs warm).

THUS, to keep your hands warm in the winter, you never need gloves or mittens.

This argument is a sound argument – no flaws or assumptions. If you have another option for keeping your hands warm, then you never truly need gloves or mittens.

In this case, the correct answer actually attacks the main premise. The correct answer says that sometimes (when it’s really really cold) putting extra layers of clothing on actually is not enough to keep your hands warm. Notice how this contradicts the premise. So, to weaken an argument you can attack a supporting premise.