Manhattan Prep’s Social Venture Scholars Program Deadline: July 6

Do you work for a non-profit? How about promote positive social change? Manhattan Prep is honored to offer special full tuition scholarships for up to 16 individuals per year (4 per quarter) who will be selected as part of Manhattan Prep’s Social Venture Scholars program. The SVS program provides selected scholars with free admission into one of Manhattan Prep’s Live Online Complete Courses (a $1299 value).

Do you work for a non-profit? How about promote positive social change? Manhattan Prep is honored to offer special full tuition scholarships for up to 16 individuals per year (4 per quarter) who will be selected as part of Manhattan Prep’s Social Venture Scholars program. The SVS program provides selected scholars with free admission into one of Manhattan Prep’s Live Online Complete Courses (a $1299 value).

These competitive scholarships are offered to individuals who (1) currently work full-time in an organization that promotes positive social change, (2) plan to use their MBA to work in a public, not-for-profit, or other venture with a social-change oriented mission, and (3) demonstrate clear financial need. The Social Venture Scholars will all enroll in a special online preparation course taught by two of Manhattan Prep’s expert instructors within one year of winning the scholarship.

The deadline is fast approaching: July 6th, 2015!

Learn more about the SVS program and apply to be one of our Social Venture Scholars here.

Studying for the GMAT? Take our free GMAT practice exam or sign up for a free GMAT trial class running all the time near you, or online. And, be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+, LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter!

GMAT Student Trends: What Do Your Fellow Test-Takers Want To Do With Their GMAT Score?

Yesterday, the Graduate Management Admissions Council (GMAC, the organization that makes the GMAT) released its annual mba.com Prospective Students Survey, a wide-ranging study of nearly 12,000 prospective GMAT-takers and graduate-school-applicants. While this survey is designed primarily to target the needs of graduate schools, there are some interesting data points that you, the aspiring student, may want to know.

Why do people want a graduate business degree?

The survey identified three main groups of people:

Career switchers (38% of respondents): these prospective students are looking to switch industries or job functions and hoping that a graduate degree will give them the boost they need to make the change successfully. People in this group are more likely than the overall pool of respondents to be age 24 or older and living in the U.S. or Canada. The size of this group has dropped by 8 percentage points in the last 5 years, perhaps not surprising as the economy has picked up since 2010.

Career enhancers (34%): these prospective students are seeking a graduate degree primarily to enhance their existing careers, whether planning to keep their current jobs or move to a new employer. People in this group are more likely than the overall pool of respondents to be female, under the age of 24, and living in Asia-Pacific, Europe, or the U.S. The size of this group hasn’t changed much in the past 5 years.

Aspiring entrepreneurs (28%): these prospective students hope to start their own businesses, possibly even before they earn their degrees, though only about 10% have already started businesses. People in this group are more likely than the overall pool of respondents to be male and living in the Middle East, Africa, Central or South Asia, or Latin America This group increased by about 9 percentage points in the past 5 years.

These three groups show some very interesting regional differentiation:

What does that mean for you? First, it’s just interesting to know.

Want kind of degree do people want to get? What kind of program do they want to attend?

The survey includes some very interesting data about the types of degrees people want. First, let’s address the two main categories of degrees: MBA and specialized. A little over half of the respondents were firmly focused on MBA degrees, while about 22% said that they want a specialized degree (such as a Master of Finance). The remaining 26% were considering both types of programs (it was unclear whether they are considering getting a dual degree or whether they just haven’t made up their mind about which type of degree to get).

Check out the graph below. Of the people considering only an MBA program, about 32% were most interested in a full-time 2-year program and 27% were aiming for an accelerated full-time 1-year program. For those considering only a specialized degree, Master of Accounting and Master of Finance programs are by far the most popular programs.

The report did not indicate what these numbers looked like in the past, but I would speculate that more people today are interested in a shorter study timeframe than 5 years ago. As the economy picks up, people don’t want to spend a full 2 years out of the work force, particularly those who are looking to stay in the same industry after graduate school. (This is just my anecdotal take based on the questions and comments I hear from students in my classes and on our forums.)

The below data reflects two combined categories: those who know they want a specialized degree and those who are still considering both types of degrees. There are distinct preferences by region for the two most popular specialized degrees.

There’s strong interest in a Master of Finance degree in Asia-Pacific and Europe. Those considering a Master of Accounting degree are most likely to live in the Asia-Pacific region or the U.S.

Want to read more?

If you’d like to read more, hop on over to the GMAC website and download the full report. If you have any interesting insights to share, or want to discuss something you find intriguing, let us know in the comments!

The GMAT® is property of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. All data cited is from GMAC’s 2015 mba.com Prospective Students Survey.

GMAT Problem Solving Strategy: Test Cases

If you’re going to do a great job on the GMAT, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless quant problems.

If you’re going to do a great job on the GMAT, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless quant problems.

This technique is especially useful for Data Sufficiency problems, but you can also use it on some Problem Solving problems, like the GMATPrep® problem below. Give yourself about 2 minutes. Go!

* “For which of the following functions f is f(x) = f(1 – x) for all x?

| (A) | f(x) = 1 – x |

| (B) | f(x) = 1 – x2 |

| (C) | f(x) = x2 – (1 – x)2 |

| (D) | f(x) = x2(1 – x)2 |

| (E) | f(x) = x / (1 – x)” |

Testing Cases is mostly what it sounds like: you will test various possible scenarios in order to narrow down the answer choices until you get to the one right answer. What’s the common characteristic that signals you can use this technique on problem solving?

The most common language will be something like “Which of the following must be true?” (or “could be true”).

The above problem doesn’t have that language, but it does have a variation: you need to find the answer choice for which the given equation is true “for all x,” which is the equivalent of asking for which answer choice the given equation is always, or must be, true.

Read more

B-School News: US News 2016 MBA Rankings Released

U.S. News & World Report today released the 2016 Best Graduate School rankings. As our friends at mbaMission have reminded us, all rankings should be approached with skepticism. “Fit” (be it academic, personal, or professional) is a far more important factor when choosing a school.

U.S. News & World Report today released the 2016 Best Graduate School rankings. As our friends at mbaMission have reminded us, all rankings should be approached with skepticism. “Fit” (be it academic, personal, or professional) is a far more important factor when choosing a school.

That said, here’s how the top 15 American business schools stack up this round:

1. Stanford University

2. Harvard University

3. University of Pennsylvania (Wharton)

4. University of Chicago (Booth)

5. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Sloan)

6. Northwestern University (Kellogg)

7. University of California, Berkeley (Haas)

8. Columbia University

9. Dartmouth College (Tuck)

10. University of Virginia (Darden)

11. New York University (Stern)

11. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (Ross)

13. Duke University (Fuqua)

13. Yale University

15. University of California, Los Angeles (Anderson)

See the full list and check out the rankings by MBA programs and specialties, here.

When Your High School Algebra is Wrong: How the GMAT Breaks Systems of Equations Rules

If you have two equations, you can solve for two variables.

If you have two equations, you can solve for two variables.

This rule is a cornerstone of algebra. It’s how we solve for values when we’re given a relationship between two unknowns:

If I can buy 2 kumquats and 3 rutabagas for $16, and 3 kumquats and 1 rutabaga for $9, how much does 1 kumquat cost?

We set up two equations:

2k + 4r = 16

3k + r = 9

Then we can use either substitution or elimination to solve. (Try it out yourself; answer* below).

On the GMAT, you’ll be using the “2 equations à 2 variables” rule to solve for a lot of word problems like the one above, especially in Problem Solving. Be careful, though! On the GMAT this rule doesn’t always apply, especially in Data Sufficiency. Here are some sneaky exceptions to the rule…

2 Equations aren’t always 2 equations

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (part 3)

Welcome to our third and final installment dedicated to those pesky maximize / minimize quant problems. If you haven’t yet reviewed the earlier installments, start with part 1 and work your way back up to this post.

I’d originally intended to do just a two-part series, but I found another GMATPrep® problem (from the free tests) covering this topic, so here you go:

“A set of 15 different integers has a median of 25 and a range of 25. What is the greatest possible integer that could be in this set?

“(A) 32

“(B) 37

“(C) 40

“(D) 43

“(E) 50”

Here’s the general process for answering quant questions—a process designed to make sure that you understand what’s going on and come up with the best plan before you dive in and solve:

Fifteen integers…that’s a little annoying because I don’t literally want to draw 15 blanks for 15 numbers. How can I shortcut this while still making sure that I’m not missing anything or causing myself to make a careless mistake?

Hmm. I could just work backwards: start from the answers and see what works. In this case, I’d want to start with answer (E), 50, since the problem asks for the greatest possible integer.

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (Part 1)

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

In this installment, we’re going to tackle two GMATPrep® questions. Next time, I’ll give you a super hard one from our own archives—just to see whether you learned the material as well as you thought you did.

Here’s your first GMATPrep problem. Go for it!

“*Three boxes of supplies have an average (arithmetic mean) weight of 7 kilograms and a median weight of 9 kilograms. What is the maximum possible weight, in kilograms, of the lightest box?

“(A) 1

“(B) 2

“(C) 3

“(D) 4

“(E) 5”

When you see the word maximum (or a synonym), sit up and take notice. This one word is going to be the determining factor in setting up this problem efficiently right from the beginning. (The word minimum or a synonym would also apply.)

When you’re asked to maximize (or minimize) one thing, you are going to have one or more decision points throughout the problem in which you are going to have to maximize or minimize some other variables. Good decisions at these points will ultimately lead to the desired maximum (or minimum) quantity.

This time, they want to maximize the lightest box. Step back from the problem a sec and picture three boxes sitting in front of you. You’re about to ship them off to a friend. Wrap your head around the dilemma: if you want to maximize the lightest box, what should you do to the other two boxes?

Note also that the problem provides some constraints. There are three boxes and the median weight is 9 kg. No variability there: the middle box must weigh 9 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

Subtract the middle box from the total to get the combined weight of the heaviest and lightest boxes: 21 – 9 = 12 kg.

The heaviest box has to be equal to or greater than 9 (because it is to the right of the median). Likewise, the lightest box has to be equal to or smaller than 9. In order to maximize the weight of the lightest box, what should you do to the heaviest box?

Minimize the weight of the heaviest box in order to maximize the weight of the lightest box. The smallest possible weight for the heaviest box is 9.

If the heaviest box is minimized to 9, and the heaviest and lightest must add up to 12, then the maximum weight for the lightest box is 3.

The correct answer is (C).

Make sense? If you’ve got it, try this harder GMATPrep problem. Set your timer for 2 minutes!

“*A certain city with a population of 132,000 is to be divided into 11 voting districts, and no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district. What is the minimum possible population that the least populated district could have?

“(A) 10,700

“(B) 10,800

“(C) 10,900

“(D) 11,000

“(E) 11,100”

Hmm. There are 11 voting districts, each with some number of people. We’re asked to find the minimum possible population in the least populated district—that is, the smallest population that any one district could possibly have.

Let’s say that District 1 has the minimum population. Because all 11 districts have to add up to 132,000 people, you’d need to maximize the population in Districts 2 through 10. How? Now, you need more information from the problem:

“no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district”

So, if the smallest district has 100 people, then the largest district could have up to 10% more, or 110 people, but it can’t have any more than that. If the smallest district has 500 people, then the largest district could have up to 550 people but that’s it.

How can you use that to figure out how to split up the 132,000 people?

In the given problem, the number of people in the smallest district is unknown, so let’s call that x. If the smallest district is x, then calculate 10% and add that figure to x: x + 0.1x = 1.1x. The largest district could be 1.1x but can’t be any larger than that.

Since you need to maximize the 10 remaining districts, set all 10 districts equal to 1.1x. As a result, there are (1.1x)(10) = 11x people in the 10 maximized districts (Districts 2 through 10), as well as the original x people in the minimized district (District 1).

The problem indicated that all 11 districts add up to 132,000, so write that out mathematically:

11x + x = 132,000

12x = 132,000

x = 11,000

The correct answer is (D).

Practice this process with any max/min problems you’ve seen recently and join me next time, when we’ll tackle a super hard problem.

Key Takeaways for Max/Min Problems:

(1) Figure out what variables are “in play”: what can you manipulate in the problem? Some of those variables will need to be maximized and some minimized in order to get to the desired answer. Figure out which is which at each step along the way.

(2) Did you make a mistake—maximize when you should have minimized or vice versa? Go through the logic again, step by step, to figure out where you were led astray and why you should have done the opposite of what you did. (This is a good process in general whenever you make a mistake: figure out why you made the mistake you made, as well as how to do the work correctly next time.)

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 4)

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams.

* “The greatest road system built in the Americas prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending from northern Ecuador through Peru to southern Chile.

“(A) Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending

“(B) Columbus was the Incan highway, over 2,500 miles in length, and extended

“(C) Columbus, the Incan highway, which was over 2,500 miles in length and extended

“(D) Columbus, the Incan highway, being over 2,500 miles in length, was extended

“(E) Columbus, the Incan highway, was over 2,500 miles long, extending”

The First Glance in this question is similar to the one from the second problem in the series. Here, the first two answers start with a noun and verb, but the next three insert a comma after the subject. Once again, this is a clue to check the core subject-verb sentence structure.

First, strip down the original sentence:

Here’s the core:

The greatest road system was the Incan highway.

(Technically, greatest is a modifier, but I’m leaving it in because it conveys important meaning. We’re not just talking about any road system. We’re talking about the greatest one in a certain era.)

The noun at the beginning of the underline, Columbus, is not the subject of the sentence but the verb was does turn out to be the main verb in the sentence. The First Glance revealed that some answers removed that verb, so check the remaining cores.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(C) The greatest road system.

“(D) The greatest road system was extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(E) The greatest road system was over 2,500 miles long.”

Answer (C) is a sentence fragment; it doesn’t contain a main verb. The other choices do contain valid core sentences, though answers (B) and (D) have funny meanings. Let’s tackle (B) first.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

When two parts of a sentence are connected by the word and, those two parallel pieces of information are not required to have a direct connection:

Yesterday, I worked for 8 hours and had dinner with my family.

Those things did not happen simultaneously. One did not lead to the other. They are both things that I did yesterday, but other than that, they don’t have anything to do with each other.

In the Columbus sentence, though, it doesn’t make sense for the two pieces of information to be separated in this way. The road system was the greatest system built to that point in time because it was so long. The fact that it extended across all of these countries is part of the point. As a result, we don’t want to present these as separate facts that have nothing to do with each other. Eliminate answer (B).

Read more

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 2)

Welcome to the second installment of our Core Sentence series; if you haven’t yet read Part 1, do so now before continuing with this segment. How has your practice been going? It’s hard to develop the ability to “grey out” parts of the sentence in your mind. Did you find that you were able to do so without writing anything down? Or did you find that the technique solidified better when you did write out the core sentence?

Welcome to the second installment of our Core Sentence series; if you haven’t yet read Part 1, do so now before continuing with this segment. How has your practice been going? It’s hard to develop the ability to “grey out” parts of the sentence in your mind. Did you find that you were able to do so without writing anything down? Or did you find that the technique solidified better when you did write out the core sentence?

Most people do have to start, in practice, by writing out the core. The goal is to be able to do everything (or almost everything) in your head by the time the real test rolls around.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams; give yourself about 1 minute 20 seconds. (You can always choose to spend a little longer, since that time is an average, not a limit; more than about 20-30 seconds longer, though, typically just indicates that you’ve gotten stuck. At that point, guess from among the remaining answers and move on.)

* “Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he quickly built his own device from an organ pipe and spectacle lenses.

“(A) Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument having been made,

“(C) Galileo, even though he had not invented the telescope, on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(D) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made,

“(E) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument being made, he”

The First Glance shows a possible sentence structure issue: The first two start with a noun and verb, while the third tosses in a comma after that subject. I’m definitely going to need to check for that verb later!

The final two start with even though, which signals a clause, but a dependent one. That means I’ll have to make sure there’s an independent clause (complete sentence) somewhere later on.

Time to read the original sentence. It’s decently complex. What’s the core sentence?

Here’s the core:

Galileo did not invent the telescope, but he built his own device.

This actually consists of two complete sentences connected by a “comma and” conjunction. There’s nothing wrong with the core on this one. Now, you have a choice. You can check the modifiers in the original sentence (and, indeed, if you did spot any problems, you’d want to go deal with those right away). If not, though, then start with those potential structure issues spotted during the first glance.

Strip out the core for the other four answers:

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but quickly built his own device.

“(C) Galileo he quickly built his own device.

“(D) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, quickly built his own device.

“(E) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, but he quickly built his own device.”

Excellent! Now we have something to work with! Answer (C) doubles the subject; we don’t need to say both Galileo and he.

Answers (D) and (E) both start with even though, creating a dependent clause. Answer (D) doesn’t have an independent clause later because the part after the comma is missing the subject he.

Note: answer (B) might appear to have the same problem as (D), but the structures are not the same. Answer (B) begins with an independent clause. In this case, it’s okay to say the subject only once at the beginning and then attach two different verbs (had not invented and built) to that subject. (You may still think this one sounds funny. More on this below.)

Answer (E) does have an independent clause later, but there’s a meaning problem. The word but already indicates a contrast. Using both even though and but to connect the two parts of the sentence is redundant.

Okay, (C), (D) and (E) have all been eliminated. Now, compare (A) and (B) directly.

“(A) Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument having been made,”

There are a couple of different ways to tackle this, but I’m going to stick to the sentence structure route, since that’s our theme today. Answer (B) does have one more clause in it, though it’s a dependent clause:

“Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard of such an optical instrument having been made, quickly built his own device.”

Now, we do have a problem with the structure! If that intervening dependent clause weren’t there at all, then the core could have been okay: Subject verb, but verb. Technically, you wouldn’t want a comma there, but that’s really the only small issue.

When, however, you introduce a dependent clause in the middle, you can’t carry that original subject, Galileo, all the way over to the second verb at the end. Instead, as with answer (D), you need a complete sentence after the dependent clause, something like:

Galileo did not invent the telescope, but when he heard that one had been made, HE quickly built his own device.

Answer (B) is also incorrect.

The correct answer is (A).

You’re halfway through! Join me next time, when we’ll take a look at another type of complex sentence structure used commonly on the GMAT.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core, part 2

(1) In the Galileo problem, only the correct answer contains a “legal” core sentence. Though there are other ways to eliminate answers on this problem, you still need to learn how to deal with structure. GMAC (the organization that makes the GMAT) has said for several years now that they are including more SC problems in which you really do have to understand the underlying meaning or sentence structure in order to get yourself all the way down to the right answer.

(2) Complex sentence structures can come in many flavors. One of the most common is the compound sentence, which consists of at least two complete sentences connected by a “comma + conjunction” or a semi-colon. The comma conjunction” structure will use the FANBOYS (For And Nor But Or Yes So). You can learn more about the FANBOYS in chapter 3 (Sentence Structure) of our 6th edition Sentence Correction Strategy Guide.

(3) A sentence can also contain dependent clauses (and the complicated sentences we see on the GMAT often do). Common words that signal a dependent clause include although, if, since, that, unless, when, and while. You can learn more about these in chapter 4 (Modifiers) of our 6ED SC guide.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 1)

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

So I’m going to write a series of articles on just this topic; welcome to part 1 (and props to my Wednesday evening GMAT Fall AA class for inspiring this series!).

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. (Note: in the solution, I’m going to discuss aspects of our SC Process; if you haven’t learned it already, go read about it right now, then come back and try this problem.)

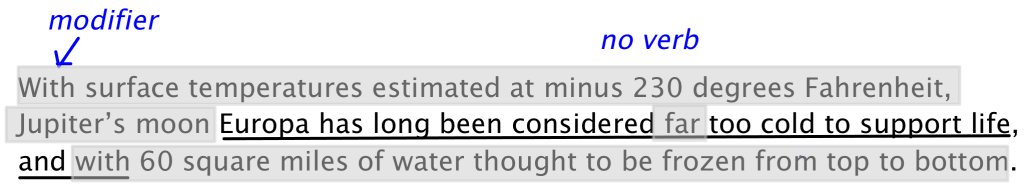

* “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit, Jupiter’s moon Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.

“(A) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with

“(B) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, its

“(C) Europa has long been considered as far too cold to support life and has

“(D) Europa, long considered as far too cold to support life, and its

“(E) Europa, long considered to be far too cold to support life, and to have”

The First Glance does help on this one, but only if you have studied sentence structure explicitly. Before I did so, I used to think: “Oh, they started with Europa because they added a comma in some answers, but that doesn’t really tell me anything.”

But I’ve learned better! What is that comma replacing? Check it out: the first three answers all have a verb following Europa. The final two don’t; that is, the verb disappears. That immediately makes me suspect sentence structure, because a sentence does have to have a verb. If you remove the main verb from one location, you have to put one in someplace else. I’ll be watching out for that when I read the sentence.

And now it’s time to do just that. As I read the sentence, I strip it down to what we call the “sentence core” in my mind. It took me a long time to develop this skill. I’ll show you the result, first, and then I’ll tell you how I learned to do it.

The “sentence core” refers to the stuff that has to be there in order to have a complete sentence. Everything else is “extra”: it may be important later, but right now, I’m ignoring it.

I greyed out the portions that are not part of the core. How does the sentence look to you?

Notice something weird: I didn’t just strip it down to a completely correct sentence. There’s something wrong with the core. In other words, the goal is not to create a correct sentence; rather, you’re using certain rules to strip to the core even when that core is incorrect.

Using this skill requires you to develop two abilities: the ability to tell what is core vs. extra and the ability to keep things that are wrong, despite the fact that they’ll make your core sound funny. The core of the sentence above is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

Clearly, that’s not a good sentence! So why did I strip out what I stripped out, and yet leave that “comma and” in there? Here was my thought process:

| Text of sentence | My thoughts: |

| “With…” | Preposition. Introduces a modifier. Can’t be the core. |

| “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit,” | Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new noun modifier. Nothing here is a subject or main verb. * |

| “Jupiter’s moon Europa” | The main noun is Europa; ignore the earlier words. |

| “Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life,” | That’s a complete sentence. Yay. |

| “, and” | A complete sentence followed by “comma and”? I’m expecting another complete sentence to follow. ** |

| “with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.” | Same deal as the beginning of the sentence! Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new modifier. Nothing here that can function as a subject or main verb. |

* Why isn’t estimated a verb?

Estimated is a past participle and can be part of a verb form, but you can’t say “Temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit.” You’d have to say “Temperatures are estimated at…” (Note: you could say “She estimated her commute to be 45 minutes from door to door.” In other words, estimated by itself can be the main verb of a sentence. In my example, though, the subject is actually doing the estimating. In the GMATPrep problem above, the temperatures can’t estimate anything!)

** Why is it that I expected another complete sentence to follow the “comma and”?

The word and is a parallelism marker; it signals that two parts of the sentence need to be made parallel. When you have one complete sentence, and you follow that with “comma and,” you need to set up another complete sentence to be parallel to that first complete sentence.

For example:

She studied all day, and she went to dinner with friends that night.

The portion before the and is a complete sentence, as is the portion after the and.

(Note: the word and can connect other things besides two complete sentences. It can connect other segments of a sentence as well, such as: She likes to eat pizza, pasta, and steak. In this case, although there is a “comma and” in the sentence, the part before the comma is not a complete sentence by itself. Rather, it is the start of a list.)

Okay, so my core is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

And that’s incorrect. Eliminate answer (A). Either that and needs to go away or, if it stays, I need to have a second complete sentence. Since you know the sentence core is at issue here, check the cores using the other answer choices:

Here are the cores written out:

“(B) Europa has long been considered too cold to support life.

“(C) Europa has long been considered as too cold to support life and has 60 square miles of water.

“(D) Europa and its 60 square miles of water.

“(E) Europa.”

(On the real test, you wouldn’t have time to write that out, but you may want to in practice in order to build expertise with this technique.)

Answers (D) and (E) don’t even have main verbs! Eliminate both. Answers (B) and (C) both contain complete sentences, but there’s something else wrong with one of them. Did you spot it?

The correct idiom is consider X Y: I consider her intelligent. There are some rare circumstances in which you can use consider as, but on the GMAT, go with consider X Y. Answers (C), (D), and (E) all use incorrect forms of the idiom.

Answer (C) also loses some meaning. The second piece of information, about the water, is meant to emphasize the fact that the moon is very cold. When you separate the two pieces of information with an and, however, they appear to be unrelated (except that they’re both facts about Europa): the moon is too cold to support life and, by the way, it also has a lot of frozen water. Still, that’s something of a judgment call; the idiom is definitive.

The correct answer is (B).

Go get some practice with this and join me next time, when we’ll try another GMATPrep problem and talk about some additional aspects of this technique.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core

(1) Generally, this is a process of elimination: you’re removing the things that cannot be part of the core sentence. With rare exceptions, prepositional phrases typically aren’t part of the core. I left the prepositional phrase of water in answers (C) and (D) because 60 square miles by itself doesn’t make any sense. In any case, prepositional phrases never contain the subject of the sentence.

(2) Other non-core-sentence clues: phrases or clauses set off by two commas, relative pronouns such as which and who, comma + -ed or comma + ing modifiers, -ed or –ing words that cannot function as the main verb (try them in a simple sentence with the same subject from the SC problem, as I did with temperatures estimated…)

(3) A complete sentence on the GMAT must have a subject and a working verb, at a minimum. You may have multiple subjects or working verbs. You could also have two complete sentences connected by a comma and conjunction (such as comma and) or a semi-colon. We’ll talk about some additional complete sentence structures next time.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.