Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (Part 2)

Last time, we discussed two GMATPrep® problems that simultaneously tested statistics and the concept of maximizing or minimizing a value. The GMAT could ask you to maximize or minimize just about anything, so the latter skill crosses many topics. Learn how to handle the nuances on these statistics problems and you’ll learn how to handle any max/min problem they might throw at you.

Last time, we discussed two GMATPrep® problems that simultaneously tested statistics and the concept of maximizing or minimizing a value. The GMAT could ask you to maximize or minimize just about anything, so the latter skill crosses many topics. Learn how to handle the nuances on these statistics problems and you’ll learn how to handle any max/min problem they might throw at you.

Feel comfortable with the two problems from the first part of this article? Then let’s kick it up a notch! The problem below was written by us (Manhattan Prep) and it’s complicated—possibly harder than anything you’ll see on the real GMAT. This problem, then, is for those who are looking for a really high quant score—or who subscribe to the philosophy that mastery includes trying stuff that’s harder than what you might see on the real test, so that you’re ready for anything.

Ready? Here you go:

“Both the average (arithmetic mean) and the median of a set of 7 numbers equal 20. If the smallest number in the set is 5 less than half the largest number, what is the largest possible number in the set?

“(A) 40

“(B) 38

“(C) 33

“(D) 32

“(E) 30”

Out of the letters A through E, which one is your favorite?

You may be thinking, “Huh? What a weird question. I don’t have a favorite.”

I don’t have one in the real world either, but I do for the GMAT, and you should, too. When you get stuck, you’re going to need to be able to let go, guess, and move on. If you haven’t been able to narrow down the answers at all, then you’ll have to make a random guess—in which case, you want to have your favorite letter ready to go.

If you have to think about what your favorite letter is, then you don’t have one yet. Pick it right now.

I’m serious. I’m not going to continue until you pick your favorite letter. Got it?

From now on, when you realize that you’re lost and you need to let go, pick your favorite letter immediately and move on. Don’t even think about it.

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (Part 1)

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

In this installment, we’re going to tackle two GMATPrep® questions. Next time, I’ll give you a super hard one from our own archives—just to see whether you learned the material as well as you thought you did.

Here’s your first GMATPrep problem. Go for it!

“*Three boxes of supplies have an average (arithmetic mean) weight of 7 kilograms and a median weight of 9 kilograms. What is the maximum possible weight, in kilograms, of the lightest box?

“(A) 1

“(B) 2

“(C) 3

“(D) 4

“(E) 5”

When you see the word maximum (or a synonym), sit up and take notice. This one word is going to be the determining factor in setting up this problem efficiently right from the beginning. (The word minimum or a synonym would also apply.)

When you’re asked to maximize (or minimize) one thing, you are going to have one or more decision points throughout the problem in which you are going to have to maximize or minimize some other variables. Good decisions at these points will ultimately lead to the desired maximum (or minimum) quantity.

This time, they want to maximize the lightest box. Step back from the problem a sec and picture three boxes sitting in front of you. You’re about to ship them off to a friend. Wrap your head around the dilemma: if you want to maximize the lightest box, what should you do to the other two boxes?

Note also that the problem provides some constraints. There are three boxes and the median weight is 9 kg. No variability there: the middle box must weigh 9 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

Subtract the middle box from the total to get the combined weight of the heaviest and lightest boxes: 21 – 9 = 12 kg.

The heaviest box has to be equal to or greater than 9 (because it is to the right of the median). Likewise, the lightest box has to be equal to or smaller than 9. In order to maximize the weight of the lightest box, what should you do to the heaviest box?

Minimize the weight of the heaviest box in order to maximize the weight of the lightest box. The smallest possible weight for the heaviest box is 9.

If the heaviest box is minimized to 9, and the heaviest and lightest must add up to 12, then the maximum weight for the lightest box is 3.

The correct answer is (C).

Make sense? If you’ve got it, try this harder GMATPrep problem. Set your timer for 2 minutes!

“*A certain city with a population of 132,000 is to be divided into 11 voting districts, and no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district. What is the minimum possible population that the least populated district could have?

“(A) 10,700

“(B) 10,800

“(C) 10,900

“(D) 11,000

“(E) 11,100”

Hmm. There are 11 voting districts, each with some number of people. We’re asked to find the minimum possible population in the least populated district—that is, the smallest population that any one district could possibly have.

Let’s say that District 1 has the minimum population. Because all 11 districts have to add up to 132,000 people, you’d need to maximize the population in Districts 2 through 10. How? Now, you need more information from the problem:

“no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district”

So, if the smallest district has 100 people, then the largest district could have up to 10% more, or 110 people, but it can’t have any more than that. If the smallest district has 500 people, then the largest district could have up to 550 people but that’s it.

How can you use that to figure out how to split up the 132,000 people?

In the given problem, the number of people in the smallest district is unknown, so let’s call that x. If the smallest district is x, then calculate 10% and add that figure to x: x + 0.1x = 1.1x. The largest district could be 1.1x but can’t be any larger than that.

Since you need to maximize the 10 remaining districts, set all 10 districts equal to 1.1x. As a result, there are (1.1x)(10) = 11x people in the 10 maximized districts (Districts 2 through 10), as well as the original x people in the minimized district (District 1).

The problem indicated that all 11 districts add up to 132,000, so write that out mathematically:

11x + x = 132,000

12x = 132,000

x = 11,000

The correct answer is (D).

Practice this process with any max/min problems you’ve seen recently and join me next time, when we’ll tackle a super hard problem.

Key Takeaways for Max/Min Problems:

(1) Figure out what variables are “in play”: what can you manipulate in the problem? Some of those variables will need to be maximized and some minimized in order to get to the desired answer. Figure out which is which at each step along the way.

(2) Did you make a mistake—maximize when you should have minimized or vice versa? Go through the logic again, step by step, to figure out where you were led astray and why you should have done the opposite of what you did. (This is a good process in general whenever you make a mistake: figure out why you made the mistake you made, as well as how to do the work correctly next time.)

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Data Sufficiency Strategy: Test Cases

If you’re going to do a great job on Data Sufficiency, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless DS problems.

If you’re going to do a great job on Data Sufficiency, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless DS problems.

Try this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. Give yourself about 2 minutes. Go!

* “On the number line, if the number k is to the left of the number t, is the product kt to the right of t?

“(1) t < 0

“(2) k < 1”

If visualizing things helps you wrap your brain around the math (it certainly helps me), sketch out a number line:

k is somewhere to the left of t, but the two actual values could be anything. Both could be positive or both negative, or k could be negative and t positive. One of the two could even be zero.

The question asks whether kt is to the right of t. That is, is the product kt greater than t by itself?

There are a million possibilities for the values of k and t, so this question is what we call a theory question: are there certain characteristics of various numbers that would produce a consistent answer? Common characteristics tested on theory problems include positive, negative, zero, simple fractions, odds, evens, primes—basically, number properties.

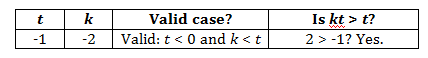

“(1) t < 0 This problem appears to be testing positive and negative, since the statement specifies that one of the values must be negative. Test some real numbers, always making sure that t is negative.

Case #1:

Testing Cases involves three consistent steps:

First, choose numbers to test in the problem

Second, make sure that you have selected a valid case. All of the givens must be true using your selected numbers.

Third, answer the question.

In this case, the answer is Yes. Now, your next strategy comes into play: try to prove the statement insufficient.

How? Ask yourself what numbers you could try that would give you the opposite answer. The first time, you got a Yes. Can you get a No?

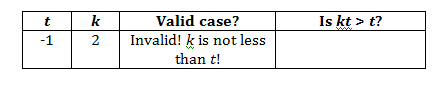

Case #2:

Careful: this is where you might make a mistake. In trying to find the opposite case, you might try a mix of numbers that is invalid. Always make sure that you have a valid case before you actually try to answer the question. Discard case 2.

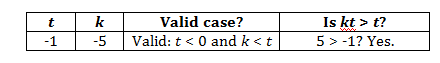

Case #3:

Hmm. We got another Yes answer. What does this mean? If you can’t come up with the opposite answer, see if you can understand why. According to this statement, t is always negative. Since k must be smaller than t, k will also always be negative.

The product kt, then, will be the product of two negative numbers, which is always positive. As a result, kt must always be larger than t, since kt is positive and t is negative.

Okay, statement (1) is sufficient. Cross off answers BCE and check out statement (2):

“(2) k < 1”

You know the drill. Test cases again!

Case #1:

You’ve got a No answer. Try to find a Yes.

Case #2:

Hmm. I got another No. What needs to happen to make kt > t? Remember what happened when you were testing statement (1): try making them both negative!

In fact, when you’re testing statement (2), see whether any of the cases you already tested for statement (1) are still valid for statement (2). If so, you can save yourself some work. Ideally, the below would be your path for statement (2), not what I first showed above:

“(2) k < 1”

Case #1:

Now, try to find your opposite answer: can you get a No?All you have to do is make sure that the case is valid. If so, you’ve already done the math, so you know that the answer is the same (in this case, Yes).

Case #2: Try something I couldn’t try before. k could be positive or even 0…

A Yes and a No add up to an insufficient answer. Eliminate answer (D).

The correct answer is (A).

Guess what? The technique can also work on some Problem Solving problems. Try it out on the following GMATPrep problem, then join me next week to discuss the answer:

* “For which of the following functions f is f(x) = f(1 – x) for all x?

“(A) f(x) = 1 – x

“(B) f(x) = 1 – x2

“(C) f(x) = x2 – (1 – x)2

“(D) f(x) = x2(1 – x)2

“(E) ![]()

Key Takeaways: Test Cases on Data Sufficiency

(1) When DS asks you a “theory” question, test cases. Theory questions allow multiple possible scenarios, or cases. Your goal is to see whether the given information provides a consistent answer.

(2) Specifically, try to disprove the statement: if you can find one Yes and one No answer, then you’re done with that statement. You know it’s insufficient. If you keep trying different kinds of numbers but getting the same answer, see whether you can think through the theory to prove to yourself that the statement really does always work. (If you can’t, but the numbers you try keep giving you one consistent answer, just go ahead and assume that the statement is sufficient. If you’ve made a mistake, you can learn from it later.)

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

Studying for the GMAT? Take our free GMAT practice exam or sign up for a free GMAT trial class running all the time near you, or online. And, be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+,LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter!

The Last 14 Days before your GMAT, Part 1: Building Your Game Plan

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

This is the original version of a piece that has since been updated. See Stacey’s latest tips on maximizing the last two weeks before your GMAT.

What’s the optimal way to spend your last 14 days before the real test? Several students have asked me this question recently, so that’s what we’re going to discuss today! There are two levels to this discussion: building a Game Plan and how to Review. We’ll discuss the former topic in the first half of this article and the latter in the second half.

What is a Game Plan?

Breaking Down B-School Admissions: A Four-Part Series

Are You Prepared for B-School Admissions?

Join Manhattan GMAT and three other leaders in the MBA admissions space—mbaMission, Poets & Quants, and MBA Career Coaches—for an invaluable series of free workshops to help you put together a successful MBA application—from your GMAT score to application essays to admissions interviews to post-acceptance internships.

We hope you’ll join us for as many events in this series as you can. Please sign up for each sessions separately via the links below—space is limited.

Session 1: Assessing Your MBA Profile,

GMAT 101: Sections, Question Types & Study Strategies

Monday, September 8 (8:00 – 10:00 PM EDT)

Click here to watch the recording

Session 2: Mastering the MBA Admissions Interview,

Conquering Two 800-Level GMAT Problems

Wednesday, September 10 (8:00 – 10:00 PM EDT)

Click here to watch the recording

Session 3: 9 Rules for Creating Standout B-School Essays,

Hitting 730: How to Get a Harvard-Level GMAT Score

Monday, September 15 (8:00 – 10:00 PM EDT)

Click here to watch the recording

Session 4: 7 Pre-MBA Steps to Your Dream Internship,

Survival Guide: 14 Days to Study for the GMAT

Wednesday, September 17 (8:00 – 10:00 PM EDT)

Sign up here.

GMAT Prep Story Problem: Make It Real Part 2

How did it go last time with the rate problem? I’ve got another story problem for you, but this time we’re going to cover a different math area.

How did it go last time with the rate problem? I’ve got another story problem for you, but this time we’re going to cover a different math area.

Just a reminder: here’s a link to the first (and long ago) article in this series: making story problems real. When the test gives you a story problem, do what you would do in the real world if your boss asked you a similar question: a back-of-the-envelope calculation to get a “close enough” answer.

If you haven’t yet read the earlier articles, go do that first. Learn how to use this method, then come back here and test your new skills on the problem below.

This is a GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. Give yourself about 2 minutes. Go!

* “Jack and Mark both received hourly wage increases of 6 percent. After the wage increases, Jack’s hourly wage was how many dollars per hour more than Mark’s?

“(1) Before the wage increases, Jack’s hourly wage was $5.00 per hour more than Mark’s.

“(2) Before the wage increases, the ratio of Jack’s hourly wage to Mark’s hourly wage was 4 to 3.”

Data sufficiency! On the one hand, awesome: we don’t have to do all the math. On the other hand, be careful: DS can get quite tricky.

Okay, you and your (colleague, friend, sister…pick a real person!) work together and you both just got hourly wage increases of 6%. (You’re Jack and your friend is Mark.) Now, the two of you are trying to figure out how much more you make.

Hmm. If you both made the same amount before, then a 6% increase would keep you both at the same level, so you’d make $0 more. If you made $100 an hour before, then you’d make $106 now, and if your colleague (I’m going to use my co-worker Whit) made $90 an hour before, then she’d be making…er, that calculation is annoying.

Actually, 6% is pretty annoying to calculate in general. Is there any way around that?

There are two broad ways; see whether you can figure either one out before you keep reading.

First, you could make sure to choose “easy” numbers. For example, if you choose $100 for your wage and half of that, $50 an hour, for Whit’s wage, the calculations become fairly easy. After you calculate the increase for you based on the easier number of $100, you know that her increase is half of yours.

Oh, wait…read statement (1). That approach isn’t going to work, since this choice limits what you can choose, and that’s going to make calculating 6% annoying.

Second, you may be able to substitute in a different percentage. Depending on the details of the problem, the specific percentage may not matter, as long as both hourly wages are increased by the same percentage.

Does that apply in this case? First, the problem asks for a relative amount: the difference in the two wages. It’s not always necessary to know the exact numbers in order to figure out a difference.

Second, the two statements continue down this path: they give relative values but not absolute values. (Yes, $5 is a real value, but it represents the difference in wages, not the actual level of wages.) As a result, you can use any percentage you want. How about 50%? That’s much easier to calculate.

Okay, back to the problem. The wages increase by 50%. They want to know the difference between your rate and Whit’s rate: Y – W = ?

“(1) Before the wage increases, Jack’s hourly wage was $5.00 per hour more than Mark’s.”

Okay, test some real numbers.

Case #1: If your wage was $10, then your new wage would be $10 + $5 = $15. In this case, Whit’s original wage had to have been $10 – $5 = $5 and so her new wage would be $5 + $2.50 = $7.50. The difference between the two new wages is $7.50.

Case #2: If your wage was $25, then your new wage would be $25 + $12.50 = $37.50. Whit’s original wage had to have been $25 – $5 = $20, so her new wage would be $20 + $10 = $30. The difference between the two new wages is…$7.50!

Wait, seriously? I was expecting the answer to be different. How can they be the same?

At this point, you have two choices: you can try one more set of numbers to see what you get or you can try to figure out whether there really is some rule that would make the difference always $7.50 no matter what.

If you try a third case, you will discover that the difference is once again $7.50. It turns out that this statement is sufficient to answer the question. Can you articulate why it must always work?

The question asks for the difference between their new hourly wages. The statement gives you the difference between their old hourly wages. If you increase the two wages by the same percentage, then you are also increasing the difference between the two wages by that exact same percentage. Since the original difference was $5, the new difference is going to be 50% greater: $5 + $2.50 = $7.50.

(Note: this would work exactly the same way if you used the original 6% given in the problem. It would just be a little more annoying to do the math, that’s all.)

Okay, statement (1) is sufficient. Cross off answers BCE and check out statement (2):

“(2) Before the wage increases, the ratio of Jack’s hourly wage to Mark’s hourly wage was 4 to 3.”

Hmm. A ratio. Maybe this one will work, too, since it also gives us something about the difference? Test a couple of cases to see. (You can still use 50% here instead of 6% in order to make the math easier.)

Case #1: If your initial wage was $4, then your new wage would be $4 + $2 = $6. Whit’s initial wage would have been $3, so her new wage would be $3 + $1.5 = $4.50. The difference between the new wages is $1.5.

Case #2: If your initial wage was $8, then your new wage would be $8 + $4 = $12. Whit’s initial wage would have been $6, so her new wage would be $6 + $3 = $9. The difference is now $3!

Statement (2) is not sufficient. The correct answer is (A).

Now, look back over the work for both statements. Are there any takeaways that could get you there faster, without having to test so many cases?

In general, if you have this set-up:

– The starting numbers both increase or decrease by the same percentage, AND

– you know the numerical difference between those two starting numbers

? Then you know that the difference will change by that same percentage. If the numbers go up by 5% each, then the difference also goes up by 5%. If you’re only asked for the difference, that number can be calculated.

If, on the other hand, the starting difference can change, then the new difference will also change. Notice that in the cases for the second statement, the difference between the old wages went from $1 in the first case to $2 in the second. If that difference is not one consistent number, then the new difference also won’t be one consistent number.

Key Takeaways: Make Stories Real

(1) Put yourself in the problem. Plug in some real numbers and test it out. Data Sufficiency problems that don’t offer real numbers for some key part of the problem are great candidates for this technique.

(2) In the problem above, the key to knowing you could test cases was the fact that they kept talking about the hourly wages but they never provided real numbers for those hourly wages. The only real number they provided represented a relative difference between the two numbers; that relative difference, however, didn’t establish what the actual wages were.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Prep Story Problem: Make It Real

In the past, we’ve talked about making story problems real. In other words, when the test gives you a story problem, don’t start making tables and writing equations and figuring out the algebraic solution. Rather, do what you would do in the real world if someone asked you this question: a back-of-the-envelope calculation (involving some math, sure, but not multiple equations with variables).

In the past, we’ve talked about making story problems real. In other words, when the test gives you a story problem, don’t start making tables and writing equations and figuring out the algebraic solution. Rather, do what you would do in the real world if someone asked you this question: a back-of-the-envelope calculation (involving some math, sure, but not multiple equations with variables).

If you haven’t yet read the article linked in the last paragraph, go do that first. Learn how to use this method, then come back here and test your new skills on the problem below.

This is a GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. Give yourself about 2 minutes. Go!

* “Machines X and Y work at their respective constant rates. How many more hours does it take machine Y, working alone, to fill a production order of a certain size than it takes machine X, working alone?

“(1) Machines X and Y, working together, fill a production order of this size in two-thirds the time that machine X, working alone, does.

“(2) Machine Y, working alone, fills a production order of this size in twice the time that machine X, working alone, does.”

You work in a factory. Your boss just came up to you and asked you this question. What do you do?

In the real world, you’d never whip out a piece of paper and start writing equations. Instead, you’d do something like this:

I need to figure out the difference between how long it takes X alone and how long it takes Y alone.

Okay, statement (1) gives me some info. Hmm, so if machine X takes 1 hour to do the job by itself, then the two machines together would take two-thirds…let’s see, that’s 40 minutes…

Wait, that number is annoying. Let’s say machine X takes 3 hours to do the job alone, so the two machines take 2 hours to do it together.

What next? Oh, right, how long does Y take? If they can do it together in 2 hours, and X takes 3 hours to do the job by itself, then X is doing 2/3 of the job in just 2 hours. So Y has to do the other 1/3 of the job in 2 hours. Read more

Memorize this and pick up 2 or 3 GMAT quant questions on the test!

Memorize what? I’m not going to tell you yet. Try this problem from the GMATPrep® free practice tests first and see whether you can spot the most efficient solution.

Memorize what? I’m not going to tell you yet. Try this problem from the GMATPrep® free practice tests first and see whether you can spot the most efficient solution.

All right, have you got an answer? How satisfied are you with your solution? If you did get an answer but you don’t feel as though you found an elegant solution, take some time to review the problem yourself before you keep reading.

Step 1: Glance Read Jot

Take a quick glance; what have you got? PS. A given equation, xy = 1. A seriously ugly-looking equation. Some fairly “nice” numbers in the answers. Hmm, maybe you should work backwards from the answers?

Jot the given info on the scrap paper.

Step 2: Reflect Organize

Oh, wait. Working backwards isn’t going to work—the answers don’t stand for just a simple variable.

Okay, what’s plan B? Does anything else jump out from the question stem?

Hey, those ugly exponents…there is one way in which they’re kind of nice. They’re both one of the three common special products. In general, when you see a special product, try rewriting the problem usually the other form of the special product.

Step 3: Work

Here’s the original expression again:

Let’s see.

Interesting. I like that for two reasons. First of all, a couple of those terms incorporate xy and the question stem told me that xy = 1, so maybe I’m heading in the right direction. Here’s what I’ve got now:

And that takes me to the second reason I like this: the two sets of exponents look awfully similar now, and they gave me a fraction to start. In general, we’re supposed to try to simplify fractions, and we do that by dividing stuff out.

How else can I write this to try to divide the similar stuff out? Wait, I’ve got it:

The numerator: ![]()

The denominator: ![]()

They’re almost identical! Both of the ![]() terms cancel out, as do the

terms cancel out, as do the ![]() terms, leaving me with:

terms, leaving me with:

![]()

I like that a lot better than the crazy thing they started me with. Okay, how do I deal with this last step?

First, be really careful. Fractions + negative exponents = messy. In order to get rid of the negative exponent, take the reciprocal of the base:

Next, dividing by 1/2 is the same as multiplying by 2:

![]()

That multiplies to 16, so the correct answer is (D).

Key Takeaways: Special Products

(1) Your math skills have to be solid. If you don’t know how to manipulate exponents or how to simplify fractions, you’re going to get this problem wrong. If you struggle to remember any of the rules, start building and drilling flash cards. If you know the rules but make careless mistakes as you work, start writing down every step and pausing to think about where you’re going before you go there. Don’t just run through everything without thinking!

(2) You need to memorize the special products and you also need to know when and how to use them. The test writers LOVE to use special products to create a seemingly impossible question with a very elegant solution. Whenever you spot any form of a special product, write the problem down using both the original form and the other form. If you’re not sure which one will lead to the answer, try the other form first, the one they didn’t give you; this is more likely to lead to the correct answer (though not always).

(3) You may not see your way to the end after just the first step. That’s okay. Look for clues that indicate that you may be on the right track, such as xy being part of the other form. If you take a few steps and come up with something totally crazy or ridiculously hard, go back to the beginning and try the other path. Often, though, you’ll find the problem simplifying itself as you get several steps in.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

Geometry – Who Said Geometry? It’s Algebra!

The GMAT quant section has many faces – there are a number of content areas, and it is best to try to master as many of them as you can before test day. It is important, however, that you not compartmentalize too much. In many of the harder questions in fact, two or more topics often show up together. You can easily find quadratics in a consecutive integer question, coordinate geometry in a probability question, number properties in a function question, for example. One common intersection of two topics that I find surprises many students is that of geometry and algebra. Many people expect a geometry question to be about marking up diagrams with values or tick marks to show equality and/or applying properties and formulas to calculate or solve. While these are no doubt important skill sets in geometry, don’t forget to pull out one of the most important skills from your GMAT tool bag – the almighty variable! x’s and y’s have a welcomed home in many a geometry question, though you might find that you are the one who has to take the initiative to put them there!

The GMAT quant section has many faces – there are a number of content areas, and it is best to try to master as many of them as you can before test day. It is important, however, that you not compartmentalize too much. In many of the harder questions in fact, two or more topics often show up together. You can easily find quadratics in a consecutive integer question, coordinate geometry in a probability question, number properties in a function question, for example. One common intersection of two topics that I find surprises many students is that of geometry and algebra. Many people expect a geometry question to be about marking up diagrams with values or tick marks to show equality and/or applying properties and formulas to calculate or solve. While these are no doubt important skill sets in geometry, don’t forget to pull out one of the most important skills from your GMAT tool bag – the almighty variable! x’s and y’s have a welcomed home in many a geometry question, though you might find that you are the one who has to take the initiative to put them there!

Take a look at this data sufficiency question from GMATPrep®

In the figure shown, the measure of ![]() PRS is how many degrees greater than the measure of

PRS is how many degrees greater than the measure of ![]() PQR?

PQR?

(1) The measure of![]() QPR is 30 degrees.

QPR is 30 degrees.

(2) The sum of the measures of ![]() PQR and

PQR and ![]() PRQ is 150 degrees.

PRQ is 150 degrees.

How did you do? Don’t feel bad if you’re a little lost on this one. This is a difficult question, though you’ll see that with the right moves it is quite doable. At the end of this discussion, you’ll even see how you could put up a good guess on this one.

As is so often the case in a data sufficiency question, the right moves here start with the stem – in rephrasing the question. Unfortunately the stem doesn’t appear to provide us with a lot of given information. As indicated in the picture, you have a 90 degree angle at ![]() PQR and that seems like all that you are given, but it’s not! There are some other inherent RELATIONSHIPS, ones that are implied by the picture. For example

PQR and that seems like all that you are given, but it’s not! There are some other inherent RELATIONSHIPS, ones that are implied by the picture. For example ![]() PRS and

PRS and ![]() PRQ sum to 180 degrees. The problem, however, is how do you CAPTURE THOSE RELATIONSHIPS? The answer is simple – you capture those relationships the way you always capture relationships in math when the relationship is between two unknown quantities – you use variables!

PRQ sum to 180 degrees. The problem, however, is how do you CAPTURE THOSE RELATIONSHIPS? The answer is simple – you capture those relationships the way you always capture relationships in math when the relationship is between two unknown quantities – you use variables!

But where should you put the variables and how many variables should you use? This last question is one that you’ll likely find yourself pondering a number of times on the GMAT. Some believe the answer to be a matter of taste. My thoughts are always use as few variables as possible. If you can capture all of the relationships that you want to capture with one variable, great. If you need two variables, so be it. The use of three or more variables would be rather uncommon in a geometry question, though you could easily see that in a word problem. Keep one thing in mind when assigning variables: the more variables you use, usually the more equations you will need to write in order to solve.

As for the first question above about where to place the variables, you can take a closer look in this question at what they are asking and use that as a guide. They ask for the (degree) difference between ![]() PRS and

PRS and ![]() PQR. Since

PQR. Since ![]() PRS is in the question, start by labeling

PRS is in the question, start by labeling ![]() PRS as x. Since

PRS as x. Since ![]() PRS and

PRS and ![]() PRQ sum to 180 degrees, you can also label

PRQ sum to 180 degrees, you can also label ![]() PRQ as (180 – x) and

PRQ as (180 – x) and ![]() RPS as (180 – x – 90) or (90 – x).

RPS as (180 – x – 90) or (90 – x).

Can you continue to label the other angles in triangle PRQ in terms of x or is it now time to place a second variable, y? Since you still have two other unknown quantities in that triangle, it’s in fact time for that y. The logical place of where to put it is on ![]() PQR since that is also part of the actual question. The temptation is to stop there – DON’T! Continue to label the final angle of the triangle,

PQR since that is also part of the actual question. The temptation is to stop there – DON’T! Continue to label the final angle of the triangle, ![]() QPR, using your newfound companions, x and y.

QPR, using your newfound companions, x and y. ![]() QPR can be labeled as [180 – y – (180 – x)] or (x – y). Now all of the angles in the triangle are labeled and you are poised and ready to craft an algebraic equation/expression to capture any other relationships that might come your way.

QPR can be labeled as [180 – y – (180 – x)] or (x – y). Now all of the angles in the triangle are labeled and you are poised and ready to craft an algebraic equation/expression to capture any other relationships that might come your way.

Before you rush off to the statements, however, there is one last step. Formulate what the question is really asking in terms of x and y. The question rephrases to “What is the value of x – y?”

Now you can finally head to the statements. Oh the joy of a fully dissected data sufficiency stem – 90% of the work has already been done!

Statement (1) tells you that the measure of ![]() QPR is 30 degrees. Using your x – y expression from the newly labeled diagram as the value of

QPR is 30 degrees. Using your x – y expression from the newly labeled diagram as the value of ![]() QPR, you can jot down the equation x – y = 30. Mission accomplished! The statement is sufficient to answer the question “what is the value of x – y?”

QPR, you can jot down the equation x – y = 30. Mission accomplished! The statement is sufficient to answer the question “what is the value of x – y?”

Statement (2) indirectly provides the same information as statement (1). If the two other angles of triangle PQR sum to 150 degrees, then ![]() QPR is 30 degrees, so the statement is sufficient as well. If you somehow missed this inference and instead directly pulled from the diagram y + (180 – x) and set that equal to 150, you’d come to the same conclusion. Either way the algebra saves the day!

QPR is 30 degrees, so the statement is sufficient as well. If you somehow missed this inference and instead directly pulled from the diagram y + (180 – x) and set that equal to 150, you’d come to the same conclusion. Either way the algebra saves the day!

The answer to the question is D, EACH statement ALONE is sufficient to answer the question asked.

NOTE here that from a strategic guessing point of view, noticing that statements (1) and (2) essentially provide the same information allows you to eliminate answer choices A, B and C: A and B because how could it be one and not the other if they are the same, and C because there is nothing gained by combining them if they provide exactly the same information.

The takeaways from this question are as follows:

(1) When a geometry question has you staring at the diagram, uncertain of how to proceed in marking things up or capturing relationships that you know exist – use variables! Those variables will help you move through the relationships just as actual values would.

(2) In data sufficiency geometry questions, when possible represent the question in algebraic form so the target becomes clear and so that the rules of algebra are there to help you assess sufficiency.

(3) Once you have assigned a variable, continue to label as much of the diagram in terms of that variable. If you need a second variable to fully label the diagram, use it. If you can get away with just one variable and still accomplish the mission, do so.

Most GMAT test-takers know that they need to develop clear strategies when it comes to different types of word problems, and most of those involve either muscling your way through the problem with some kind of practical approach (picking numbers, visualizing, back-solving, logical reasoning) or writing out algebraic equations and solving. There are of course pluses and minuses to all of the approaches and those need to be weighed by each person on an individual basis. What few realize, however, is that geometry questions can also demonstrate that level of complexity and thus can often also be solved with the tools of algebra. When actual values are few and far between, don’t hesitate to pull out an “x” (and possibly also a “y”) and see what kind of equations/expressions you can cook up.

For more practice in “algebrating” a geometry question, please see OG 13th DS 79 and Quant Supplement 2nd editions PS 157, 162 and DS 60, 114 and 123.

The 4 GMAT Math Strategies Everyone Must Master: Testing Cases Redux

A while back, we talked about the 4 GMAT math strategies that everyone needs to master. Today, I’ve got some additional practice for you with regard to one of those strategies: Testing Cases.

A while back, we talked about the 4 GMAT math strategies that everyone needs to master. Today, I’ve got some additional practice for you with regard to one of those strategies: Testing Cases.

Try this GMATPrep® problem:

* ” If xy + z = x(y + z), which of the following must be true?

“(A) x = 0 and z = 0

“(B) x = 1 and y = 1

“(C) y = 1 and z = 0

“(D) x = 1 or y = 0

“(E) x = 1 or z = 0

How did it go?

This question is called a “theory” question: there are just variables, no real numbers, and the answer depends on some characteristic of a category of numbers, not a specific number or set of numbers. Problem solving theory questions also usually ask what must or could be true (or what must not be true). When we have these kinds of questions, we can use theory to solve—but that can get very confusing very quickly. Testing real numbers to “prove” the theory to yourself will make the work easier.

The question stem contains a given equation:

xy + z = x(y + z)

Whenever the problem gives you a complicated equation, make your life easier: try to simplify the equation before you do any more work.

xy + z = x(y + z)

xy + z = xy + xz

z = xz

Very interesting! The y term subtracts completely out of the equation. What is the significance of that piece of info?

Nothing absolutely has to be true about the variable y. Glance at your answers. You can cross off (B), (C), and (D) right now!

Next, notice something. I stopped at z = xz. I didn’t divide both sides by z. Why?

In general, never divide by a variable unless you know that the variable does not equal zero. Dividing by zero is an “illegal” move in algebra—and it will cause you to lose a possible solution to the equation, increasing your chances of answering the problem incorrectly.

The best way to finish off this problem is to test possible cases. Notice a couple of things about the answers. First, they give you very specific possibilities to test; you don’t even have to come up with your own numbers to try. Second, answer (A) says that both pieces must be true (“and”) while answer (E) says “or.” Keep that in mind while working through the rest of the problem.

z = xz

Let’s see. z = 0 would make this equation true, so that is one possibility. This shows up in both remaining answers.

If x = 0, then the right-hand side would become 0. In that case, z would also have to be 0 in order for the equation to be true. That matches answer (A).

If x = 1, then it doesn’t matter what z is; the equation will still be true. That matches answer (E).

Wait a second—what’s going on? Both answers can’t be correct.

Be careful about how you test cases. The question asks what MUST be true. Go back to the starting point that worked for both answers: z = 0.

It’s true that, for example, 0 = (3)(0).

Does z always have to equal 0? Can you come up with a case where z does not equal 0 but the equation is still true?

Try 2 = (1)(2). In this case, z = 2 and x = 1, and the equation is true. Here’s the key to the “and” vs. “or” language. If z = 0, then the equation is always 0 = 0, but if not, then x must be 1; in that case, the equation is z = z. In other words, either x = 1 OR z = 0.

The correct answer is (E).

The above reasoning also proves why answer (A) could be true but doesn’t always have to be true. If both variables are 0, then the equation works, but other combinations are also possible, such as z = 2 and x = 1.

Key Takeaways: Test Cases on Theory Problems

(1) If you didn’t simplify the original equation, and so didn’t know that y didn’t matter, then you still could’ve tested real numbers to narrow down the answers, but it would’ve taken longer. Whenever possible, simplify the given information to make your work easier.

(2) Must Be True problems are usually theory problems. Test some real numbers to help yourself understand the theory and knock out answers. Where possible, use the answer choices to help you decide what to test.

(3) Be careful about how you test those cases! On a must be true question, some or all of the wrong answers could be true some of the time; you’ll need to figure out how to test the cases in such a way that you figure out what must be true all the time, not just what could be true.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.