GMAT Problem Solving Strategy: Test Cases

If you’re going to do a great job on the GMAT, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless quant problems.

If you’re going to do a great job on the GMAT, then you’ve got to know how to Test Cases. This strategy will help you on countless quant problems.

This technique is especially useful for Data Sufficiency problems, but you can also use it on some Problem Solving problems, like the GMATPrep® problem below. Give yourself about 2 minutes. Go!

* “For which of the following functions f is f(x) = f(1 – x) for all x?

| (A) | f(x) = 1 – x |

| (B) | f(x) = 1 – x2 |

| (C) | f(x) = x2 – (1 – x)2 |

| (D) | f(x) = x2(1 – x)2 |

| (E) | f(x) = x / (1 – x)” |

Testing Cases is mostly what it sounds like: you will test various possible scenarios in order to narrow down the answer choices until you get to the one right answer. What’s the common characteristic that signals you can use this technique on problem solving?

The most common language will be something like “Which of the following must be true?” (or “could be true”).

The above problem doesn’t have that language, but it does have a variation: you need to find the answer choice for which the given equation is true “for all x,” which is the equivalent of asking for which answer choice the given equation is always, or must be, true.

Read more

Free Webinar Series: 5 Steps to Your Dream MBA

Are You Prepared for B-School Admissions?

Join Manhattan GMAT and two other leaders in the MBA admissions space— mbaMission and MBA Career Coaches

—for an invaluable series of free workshops to help you put together a successful MBA application, from your GMAT score to application essays to admissions interviews to post-acceptance internships. We hope you will join us for as many events in this series as you can. Please sign up for each sessions separately via the links below—space is limited.

Session 1: Assessing Your MBA Profile and GMAT vs. GRE

Tuesday, March 24, 2015 (7:30- 9:00 PM EDT) SIGN UP HERE

Session 2: Selecting Your Target MBA Program and How

to Study for the GMAT in Two Weeks

Tuesday, March 31, 2015 (7:30- 9:00 PM EDT) SIGN UP HERE

Session 3: Writing Standout B-School Admissions Essays

and Advanced GMAT: 700+ Level Sentence Correction

Tuesday, April 7, 2015 (7:30- 9:00 PM EDT) SIGN UP HERE

Session 4: Five Pre-MBA Steps to Landing Your Dream Internship and

Advanced GMAT: 700+ Level Quant Strategy

Tuesday, April 14, 2015 (7:30- 9:00 PM EDT) SIGN UP HERE

Session 5: Questions and Answers with MBA Admissions Officers

Tuesday, April 21, 2015 (7:30- 9:00 PM EDT) SIGN UP HERE

Want a Better GMAT Score? Go to Sleep!

This is going to be a short post. It will also possibly have the biggest impact on your study of anything you do all day (or all month!).

This is going to be a short post. It will also possibly have the biggest impact on your study of anything you do all day (or all month!).

When people ramp up to study for the GMAT, they typically find the time to study by cutting down on other activities—no more Thursday night happy hour with the gang or Sunday brunch with the family until the test is over.

There are two activities, though, that you should never cut—and, unfortunately, I talk to students every day who do cut these two activities. I hear this so much that I abandoned what I was going to cover today and wrote this instead. We’re not going to cover any problems or discuss specific test strategies in this article. We’re going to discuss something infinitely more important!

#1: You must get a full night’s sleep

Period. Never cut your sleep in order to study for this test. NEVER.

Your brain does not work as well when trying to function on less sleep than it needs. You know this already. Think back to those times that you pulled an all-nighter to study for a final or get a client presentation out the door. You may have felt as though you were flying high in the moment, adrenaline coursing through your veins. Afterwards, though, your brain felt fuzzy and slow. Worse, you don’t really have great memories of exactly what you did—maybe you did okay on the test that morning, but afterwards, it was as though you’d never studied the material at all.

There are two broad (and very negative) symptoms of this mental fatigue that you need to avoid when studying for the GMAT (and doing other mentally-taxing things in life). First, when you are mentally fatigued, you can’t function as well as normal in the moment. You’re going to make more careless mistakes and you’re just going to think more slowly and painfully than usual.

Read more

When Your High School Algebra is Wrong: How the GMAT Breaks Systems of Equations Rules

If you have two equations, you can solve for two variables.

If you have two equations, you can solve for two variables.

This rule is a cornerstone of algebra. It’s how we solve for values when we’re given a relationship between two unknowns:

If I can buy 2 kumquats and 3 rutabagas for $16, and 3 kumquats and 1 rutabaga for $9, how much does 1 kumquat cost?

We set up two equations:

2k + 4r = 16

3k + r = 9

Then we can use either substitution or elimination to solve. (Try it out yourself; answer* below).

On the GMAT, you’ll be using the “2 equations à 2 variables” rule to solve for a lot of word problems like the one above, especially in Problem Solving. Be careful, though! On the GMAT this rule doesn’t always apply, especially in Data Sufficiency. Here are some sneaky exceptions to the rule…

2 Equations aren’t always 2 equations

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (part 3)

Welcome to our third and final installment dedicated to those pesky maximize / minimize quant problems. If you haven’t yet reviewed the earlier installments, start with part 1 and work your way back up to this post.

I’d originally intended to do just a two-part series, but I found another GMATPrep® problem (from the free tests) covering this topic, so here you go:

“A set of 15 different integers has a median of 25 and a range of 25. What is the greatest possible integer that could be in this set?

“(A) 32

“(B) 37

“(C) 40

“(D) 43

“(E) 50”

Here’s the general process for answering quant questions—a process designed to make sure that you understand what’s going on and come up with the best plan before you dive in and solve:

Fifteen integers…that’s a little annoying because I don’t literally want to draw 15 blanks for 15 numbers. How can I shortcut this while still making sure that I’m not missing anything or causing myself to make a careless mistake?

Hmm. I could just work backwards: start from the answers and see what works. In this case, I’d want to start with answer (E), 50, since the problem asks for the greatest possible integer.

Read more

How to Infer on the GMAT

We’re going to kill two birds with one stone in this week’s article.

We’re going to kill two birds with one stone in this week’s article.

Inference questions pop up on both Critical Reasoning (CR) and Reading Comprehension (RC), so you definitely want to master these. Good news: the kind of thinking the test-writers want is the same for both question types. Learn how to do Inference questions on one type and you’ll know what you need to do for the other!

That’s actually only one bird. Here’s the second: both CR and RC can give you science-based text, and that science-y text can get pretty confusing. How can you avoid getting sucked into the technical detail, yet still be able to answer the question asked? Read on.

Try this GMATPrep® CR problem out (it’s from the free practice tests) and then we’ll talk about it. Give yourself about 2 minutes (though it’s okay to stretch to 2.5 minutes on a CR as long as you are making progress.)

“Increases in the level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in the human bloodstream lower bloodstream cholesterol levels by increasing the body’s capacity to rid itself of excess cholesterol. Levels of HDL in the bloodstream of some individuals are significantly increased by a program of regular exercise and weight reduction.

“Which of the following can be correctly inferred from the statements above?

“(A) Individuals who are underweight do not run any risk of developing high levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream.

“(B) Individuals who do not exercise regularly have a high risk of developing high levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream late in life.

“(C) Exercise and weight reduction are the most effective methods of lowering bloodstream cholesterol levels in humans.

“(D) A program of regular exercise and weight reduction lowers cholesterol levels in the bloodstream of some individuals.

“(E) Only regular exercise is necessary to decrease cholesterol levels in the bloodstream of individuals of average weight.”

Got an answer? (If not, pick one anyway. Pretend it’s the real test and just make a guess.) Before we dive into the solution, let’s talk a little bit about what Inference questions are asking us to do.

Inference questions are sometimes also called Draw a Conclusion questions. I don’t like that title, though, because it can be misleading. Think about a typical CR argument: they usually include a conclusion that is…well…not a solid conclusion. There are holes in the argument, and then they ask you to Strengthen it or Weaken it or something like that.

Read more

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 4)

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams.

* “The greatest road system built in the Americas prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending from northern Ecuador through Peru to southern Chile.

“(A) Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending

“(B) Columbus was the Incan highway, over 2,500 miles in length, and extended

“(C) Columbus, the Incan highway, which was over 2,500 miles in length and extended

“(D) Columbus, the Incan highway, being over 2,500 miles in length, was extended

“(E) Columbus, the Incan highway, was over 2,500 miles long, extending”

The First Glance in this question is similar to the one from the second problem in the series. Here, the first two answers start with a noun and verb, but the next three insert a comma after the subject. Once again, this is a clue to check the core subject-verb sentence structure.

First, strip down the original sentence:

Here’s the core:

The greatest road system was the Incan highway.

(Technically, greatest is a modifier, but I’m leaving it in because it conveys important meaning. We’re not just talking about any road system. We’re talking about the greatest one in a certain era.)

The noun at the beginning of the underline, Columbus, is not the subject of the sentence but the verb was does turn out to be the main verb in the sentence. The First Glance revealed that some answers removed that verb, so check the remaining cores.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(C) The greatest road system.

“(D) The greatest road system was extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(E) The greatest road system was over 2,500 miles long.”

Answer (C) is a sentence fragment; it doesn’t contain a main verb. The other choices do contain valid core sentences, though answers (B) and (D) have funny meanings. Let’s tackle (B) first.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

When two parts of a sentence are connected by the word and, those two parallel pieces of information are not required to have a direct connection:

Yesterday, I worked for 8 hours and had dinner with my family.

Those things did not happen simultaneously. One did not lead to the other. They are both things that I did yesterday, but other than that, they don’t have anything to do with each other.

In the Columbus sentence, though, it doesn’t make sense for the two pieces of information to be separated in this way. The road system was the greatest system built to that point in time because it was so long. The fact that it extended across all of these countries is part of the point. As a result, we don’t want to present these as separate facts that have nothing to do with each other. Eliminate answer (B).

Read more

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 1)

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

So I’m going to write a series of articles on just this topic; welcome to part 1 (and props to my Wednesday evening GMAT Fall AA class for inspiring this series!).

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. (Note: in the solution, I’m going to discuss aspects of our SC Process; if you haven’t learned it already, go read about it right now, then come back and try this problem.)

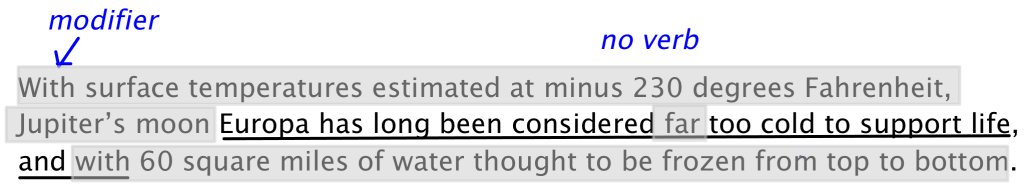

* “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit, Jupiter’s moon Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.

“(A) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with

“(B) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, its

“(C) Europa has long been considered as far too cold to support life and has

“(D) Europa, long considered as far too cold to support life, and its

“(E) Europa, long considered to be far too cold to support life, and to have”

The First Glance does help on this one, but only if you have studied sentence structure explicitly. Before I did so, I used to think: “Oh, they started with Europa because they added a comma in some answers, but that doesn’t really tell me anything.”

But I’ve learned better! What is that comma replacing? Check it out: the first three answers all have a verb following Europa. The final two don’t; that is, the verb disappears. That immediately makes me suspect sentence structure, because a sentence does have to have a verb. If you remove the main verb from one location, you have to put one in someplace else. I’ll be watching out for that when I read the sentence.

And now it’s time to do just that. As I read the sentence, I strip it down to what we call the “sentence core” in my mind. It took me a long time to develop this skill. I’ll show you the result, first, and then I’ll tell you how I learned to do it.

The “sentence core” refers to the stuff that has to be there in order to have a complete sentence. Everything else is “extra”: it may be important later, but right now, I’m ignoring it.

I greyed out the portions that are not part of the core. How does the sentence look to you?

Notice something weird: I didn’t just strip it down to a completely correct sentence. There’s something wrong with the core. In other words, the goal is not to create a correct sentence; rather, you’re using certain rules to strip to the core even when that core is incorrect.

Using this skill requires you to develop two abilities: the ability to tell what is core vs. extra and the ability to keep things that are wrong, despite the fact that they’ll make your core sound funny. The core of the sentence above is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

Clearly, that’s not a good sentence! So why did I strip out what I stripped out, and yet leave that “comma and” in there? Here was my thought process:

| Text of sentence | My thoughts: |

| “With…” | Preposition. Introduces a modifier. Can’t be the core. |

| “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit,” | Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new noun modifier. Nothing here is a subject or main verb. * |

| “Jupiter’s moon Europa” | The main noun is Europa; ignore the earlier words. |

| “Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life,” | That’s a complete sentence. Yay. |

| “, and” | A complete sentence followed by “comma and”? I’m expecting another complete sentence to follow. ** |

| “with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.” | Same deal as the beginning of the sentence! Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new modifier. Nothing here that can function as a subject or main verb. |

* Why isn’t estimated a verb?

Estimated is a past participle and can be part of a verb form, but you can’t say “Temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit.” You’d have to say “Temperatures are estimated at…” (Note: you could say “She estimated her commute to be 45 minutes from door to door.” In other words, estimated by itself can be the main verb of a sentence. In my example, though, the subject is actually doing the estimating. In the GMATPrep problem above, the temperatures can’t estimate anything!)

** Why is it that I expected another complete sentence to follow the “comma and”?

The word and is a parallelism marker; it signals that two parts of the sentence need to be made parallel. When you have one complete sentence, and you follow that with “comma and,” you need to set up another complete sentence to be parallel to that first complete sentence.

For example:

She studied all day, and she went to dinner with friends that night.

The portion before the and is a complete sentence, as is the portion after the and.

(Note: the word and can connect other things besides two complete sentences. It can connect other segments of a sentence as well, such as: She likes to eat pizza, pasta, and steak. In this case, although there is a “comma and” in the sentence, the part before the comma is not a complete sentence by itself. Rather, it is the start of a list.)

Okay, so my core is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

And that’s incorrect. Eliminate answer (A). Either that and needs to go away or, if it stays, I need to have a second complete sentence. Since you know the sentence core is at issue here, check the cores using the other answer choices:

Here are the cores written out:

“(B) Europa has long been considered too cold to support life.

“(C) Europa has long been considered as too cold to support life and has 60 square miles of water.

“(D) Europa and its 60 square miles of water.

“(E) Europa.”

(On the real test, you wouldn’t have time to write that out, but you may want to in practice in order to build expertise with this technique.)

Answers (D) and (E) don’t even have main verbs! Eliminate both. Answers (B) and (C) both contain complete sentences, but there’s something else wrong with one of them. Did you spot it?

The correct idiom is consider X Y: I consider her intelligent. There are some rare circumstances in which you can use consider as, but on the GMAT, go with consider X Y. Answers (C), (D), and (E) all use incorrect forms of the idiom.

Answer (C) also loses some meaning. The second piece of information, about the water, is meant to emphasize the fact that the moon is very cold. When you separate the two pieces of information with an and, however, they appear to be unrelated (except that they’re both facts about Europa): the moon is too cold to support life and, by the way, it also has a lot of frozen water. Still, that’s something of a judgment call; the idiom is definitive.

The correct answer is (B).

Go get some practice with this and join me next time, when we’ll try another GMATPrep problem and talk about some additional aspects of this technique.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core

(1) Generally, this is a process of elimination: you’re removing the things that cannot be part of the core sentence. With rare exceptions, prepositional phrases typically aren’t part of the core. I left the prepositional phrase of water in answers (C) and (D) because 60 square miles by itself doesn’t make any sense. In any case, prepositional phrases never contain the subject of the sentence.

(2) Other non-core-sentence clues: phrases or clauses set off by two commas, relative pronouns such as which and who, comma + -ed or comma + ing modifiers, -ed or –ing words that cannot function as the main verb (try them in a simple sentence with the same subject from the SC problem, as I did with temperatures estimated…)

(3) A complete sentence on the GMAT must have a subject and a working verb, at a minimum. You may have multiple subjects or working verbs. You could also have two complete sentences connected by a comma and conjunction (such as comma and) or a semi-colon. We’ll talk about some additional complete sentence structures next time.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

Top GMAT Prep Courses: Interview with Manhattan Prep Instructor Ron Purewal

The following excerpt comes from Top GMAT Prep Courses, a helpful resource for comparing your GMAT prep options, gathering in-depth course reviews, and receiving exclusive discounts. Top GMAT Prep Courses had the chance to connect with Ron Purewal, one of Manhattan Prep’s veteran GMAT instructors, to ask questions about the GMAT that we hope all prospective MBA candidates will benefit from. Want more? Head on over to the full article!

The following excerpt comes from Top GMAT Prep Courses, a helpful resource for comparing your GMAT prep options, gathering in-depth course reviews, and receiving exclusive discounts. Top GMAT Prep Courses had the chance to connect with Ron Purewal, one of Manhattan Prep’s veteran GMAT instructors, to ask questions about the GMAT that we hope all prospective MBA candidates will benefit from. Want more? Head on over to the full article!

What are the most common misconceptions of the GMAT that you notice on a regular basis?

“There are two BIG misconceptions in play here.

The first is “knowledge.” Too many people view this test as a monumental task of memorization. A test of knowing stuff. If you’re new to this exam, it’s understandable that you might think this way. After all, that’s how tests have always worked at school, right? Right. And that’s exactly why the GMAT doesn’t work that way. Think about it for a sec: When it comes to those tests, the tests of knowing stuff, you already have 16 or more years of experience (and grades) under your belt. If the GMAT were yet another one of those tests, it would have no utility. It wouldn’t exist. Instead, the GMAT is precisely the opposite: It’s a test designed to be challenging, and to test skills relevant to business school, while requiring as little concrete knowledge as possible.

If you’re skeptical, go work a few GMAT problems. Then, when the smoke clears, take an inventory of all the stuff you had to know to solve the problem, as opposed to the thought process itself. You’ll be surprised by how short the list is, and how elementary the things are. The challenge isn’t the “what;” it’s the “how.” …Continue reading for the second misconception.

How common is it for a student to raise his or her GMAT score 100 points or more, and what is the largest GMAT score increase you’ve personally seen while working at Manhattan Prep?

“We’ve seen such increases from many of our students. I’ve even seen a few increases of more than 300 points, from English learners who made parallel progress on the GMAT and in English itself. I don’t have statistics, but what I can give you is far more important: a list of traits that those successful students have in common.

1) They are flexible and willing to change. They do not cling stubbornly to “preferred” or “textbook” ways of solving problems; instead, they simply collect as many different strategies as possible.

2) They are resilient. When an approach fails, they don’t internalize it as “defeat,” and they don’t keep trying the same things over and over. They just dump the approach that isn’t working, and look for something different. If they come up empty, they simply disengage, guess, and move on.

3) They are balanced. They make time to engage with the GMAT, but they don’t subordinate their entire lives to it. They study three, four, five days a week—not zero, and not seven. They review problems when they’re actually primed to learn; they don’t put in hours just for the sake of putting in hours. If they’re overwhelmed, exhausted, or distressed, they’ll shut the books and hit them another day. In short, they stay sane… Continue reading for more traits of successful students.

Studying for the GMAT? Take our free GMAT practice exam or sign up for a free GMAT trial class running all the time near you, or online. And, be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+,LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter!

The Last 14 Days before your GMAT, Part 1: Building Your Game Plan

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

This is the original version of a piece that has since been updated. See Stacey’s latest tips on maximizing the last two weeks before your GMAT.

What’s the optimal way to spend your last 14 days before the real test? Several students have asked me this question recently, so that’s what we’re going to discuss today! There are two levels to this discussion: building a Game Plan and how to Review. We’ll discuss the former topic in the first half of this article and the latter in the second half.