GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 1)

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

So I’m going to write a series of articles on just this topic; welcome to part 1 (and props to my Wednesday evening GMAT Fall AA class for inspiring this series!).

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. (Note: in the solution, I’m going to discuss aspects of our SC Process; if you haven’t learned it already, go read about it right now, then come back and try this problem.)

* “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit, Jupiter’s moon Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.

“(A) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with

“(B) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, its

“(C) Europa has long been considered as far too cold to support life and has

“(D) Europa, long considered as far too cold to support life, and its

“(E) Europa, long considered to be far too cold to support life, and to have”

The First Glance does help on this one, but only if you have studied sentence structure explicitly. Before I did so, I used to think: “Oh, they started with Europa because they added a comma in some answers, but that doesn’t really tell me anything.”

But I’ve learned better! What is that comma replacing? Check it out: the first three answers all have a verb following Europa. The final two don’t; that is, the verb disappears. That immediately makes me suspect sentence structure, because a sentence does have to have a verb. If you remove the main verb from one location, you have to put one in someplace else. I’ll be watching out for that when I read the sentence.

And now it’s time to do just that. As I read the sentence, I strip it down to what we call the “sentence core” in my mind. It took me a long time to develop this skill. I’ll show you the result, first, and then I’ll tell you how I learned to do it.

The “sentence core” refers to the stuff that has to be there in order to have a complete sentence. Everything else is “extra”: it may be important later, but right now, I’m ignoring it.

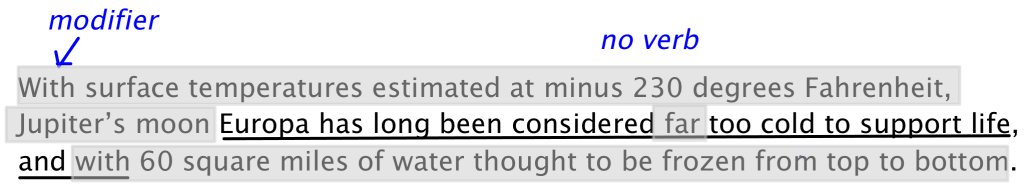

I greyed out the portions that are not part of the core. How does the sentence look to you?

Notice something weird: I didn’t just strip it down to a completely correct sentence. There’s something wrong with the core. In other words, the goal is not to create a correct sentence; rather, you’re using certain rules to strip to the core even when that core is incorrect.

Using this skill requires you to develop two abilities: the ability to tell what is core vs. extra and the ability to keep things that are wrong, despite the fact that they’ll make your core sound funny. The core of the sentence above is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

Clearly, that’s not a good sentence! So why did I strip out what I stripped out, and yet leave that “comma and” in there? Here was my thought process:

| Text of sentence | My thoughts: |

| “With…” | Preposition. Introduces a modifier. Can’t be the core. |

| “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit,” | Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new noun modifier. Nothing here is a subject or main verb. * |

| “Jupiter’s moon Europa” | The main noun is Europa; ignore the earlier words. |

| “Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life,” | That’s a complete sentence. Yay. |

| “, and” | A complete sentence followed by “comma and”? I’m expecting another complete sentence to follow. ** |

| “with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.” | Same deal as the beginning of the sentence! Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new modifier. Nothing here that can function as a subject or main verb. |

* Why isn’t estimated a verb?

Estimated is a past participle and can be part of a verb form, but you can’t say “Temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit.” You’d have to say “Temperatures are estimated at…” (Note: you could say “She estimated her commute to be 45 minutes from door to door.” In other words, estimated by itself can be the main verb of a sentence. In my example, though, the subject is actually doing the estimating. In the GMATPrep problem above, the temperatures can’t estimate anything!)

** Why is it that I expected another complete sentence to follow the “comma and”?

The word and is a parallelism marker; it signals that two parts of the sentence need to be made parallel. When you have one complete sentence, and you follow that with “comma and,” you need to set up another complete sentence to be parallel to that first complete sentence.

For example:

She studied all day, and she went to dinner with friends that night.

The portion before the and is a complete sentence, as is the portion after the and.

(Note: the word and can connect other things besides two complete sentences. It can connect other segments of a sentence as well, such as: She likes to eat pizza, pasta, and steak. In this case, although there is a “comma and” in the sentence, the part before the comma is not a complete sentence by itself. Rather, it is the start of a list.)

Okay, so my core is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

And that’s incorrect. Eliminate answer (A). Either that and needs to go away or, if it stays, I need to have a second complete sentence. Since you know the sentence core is at issue here, check the cores using the other answer choices:

Here are the cores written out:

“(B) Europa has long been considered too cold to support life.

“(C) Europa has long been considered as too cold to support life and has 60 square miles of water.

“(D) Europa and its 60 square miles of water.

“(E) Europa.”

(On the real test, you wouldn’t have time to write that out, but you may want to in practice in order to build expertise with this technique.)

Answers (D) and (E) don’t even have main verbs! Eliminate both. Answers (B) and (C) both contain complete sentences, but there’s something else wrong with one of them. Did you spot it?

The correct idiom is consider X Y: I consider her intelligent. There are some rare circumstances in which you can use consider as, but on the GMAT, go with consider X Y. Answers (C), (D), and (E) all use incorrect forms of the idiom.

Answer (C) also loses some meaning. The second piece of information, about the water, is meant to emphasize the fact that the moon is very cold. When you separate the two pieces of information with an and, however, they appear to be unrelated (except that they’re both facts about Europa): the moon is too cold to support life and, by the way, it also has a lot of frozen water. Still, that’s something of a judgment call; the idiom is definitive.

The correct answer is (B).

Go get some practice with this and join me next time, when we’ll try another GMATPrep problem and talk about some additional aspects of this technique.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core

(1) Generally, this is a process of elimination: you’re removing the things that cannot be part of the core sentence. With rare exceptions, prepositional phrases typically aren’t part of the core. I left the prepositional phrase of water in answers (C) and (D) because 60 square miles by itself doesn’t make any sense. In any case, prepositional phrases never contain the subject of the sentence.

(2) Other non-core-sentence clues: phrases or clauses set off by two commas, relative pronouns such as which and who, comma + -ed or comma + ing modifiers, -ed or –ing words that cannot function as the main verb (try them in a simple sentence with the same subject from the SC problem, as I did with temperatures estimated…)

(3) A complete sentence on the GMAT must have a subject and a working verb, at a minimum. You may have multiple subjects or working verbs. You could also have two complete sentences connected by a comma and conjunction (such as comma and) or a semi-colon. We’ll talk about some additional complete sentence structures next time.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: Where do I start? (Part 3)

Welcome to the third part of our series focusing on the First Glance in Sentence Correction. If you haven’t read the previous installments yet, you can start with how to find a starting point on a Sentence Correction problem when the starting point doesn’t leap out at you.

Welcome to the third part of our series focusing on the First Glance in Sentence Correction. If you haven’t read the previous installments yet, you can start with how to find a starting point on a Sentence Correction problem when the starting point doesn’t leap out at you.

Try out the First Glance on the below problem and see what happens! This is a GMATPrep® problem from the free exams.

* “Most of the purported health benefits of tea comes from antioxidants—compounds also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C that inhibit the formation of plaque along the body’s blood vessels.

“(A) comes from antioxidants—compounds also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C that

“(B) comes from antioxidants—compounds that are also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C, and they

“(C) come from antioxidants—compounds also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C, and

“(D) come from antioxidants—compounds that are also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C and that

“(E) come from antioxidants—compounds also found in beta carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin C, and they”

The First Glance definitely helps on this one: comes vs. come is a singular vs. plural verb split, indicating a subject-verb agreement issue. Now, when you read the original sentence, you know to find the subject.

So what is the subject of the sentence? It’s not the singular tea, though it’s tempting to think so. The subject is actually the word most, which is a SANAM pronoun.

The SANAM pronouns: Some, Any, None, All, More / Most

These pronouns can be singular or plural, depending on the context of the sentence. Consider these examples:

GMAT Sentence Correction: Where do I start? (Part 2)

Last time, we talked about how to find a starting point on a Sentence Correction problem when the starting point doesn’t leap out at you. If you haven’t read that article yet, go ahead and do so.

Last time, we talked about how to find a starting point on a Sentence Correction problem when the starting point doesn’t leap out at you. If you haven’t read that article yet, go ahead and do so.

The first step of the SC process is a First Glance, something that didn’t help out a whole lot on last week’s problem. Let’s try out the First Glance again and see what happens!

This GMATPrep® problem is from the free exams.

* “Often incorrectly referred to as a tidal wave, a tsunami, a seismic sea wave that can reach up to 150 miles per hour in speed and 200 feet high, is caused by underwater earthquakes or volcanic eruptions.

“(A) up to 150 miles per hour in speed and 200 feet high, is

“(B) up to 150 miles per hour in speed and heights of up to 200 feet, is

“(C) speeds of up to 150 miles per hour and 200 feet high, are

“(D) speeds of up to 150 miles per hour and heights of up to 200 feet, is

“(E) speeds of up to 150 miles per hour and as high as 200 feet, are”

What did you do for the First Glance? The glance is designed to give you an upfront hint about one issue that the sentence might be testing before you actually start reading the full sentence. Take a look at the beginning of the underline, including the beginning of all five answer choices.

The split is between up to and speeds of up to. There isn’t an obvious grammar rule here, so the issue is likely to revolve around meaning: do we need to say speeds of or is it enough to say just up to?

Think about this while reading the original sentence. What do you think?

The phrase reach up to could go in several different directions—is it going to say up to 150 miles in length? up to 150 feet high?—so it’s preferable to clarify right up front that the wave is reaching speeds of up to 150 miles per hour.

In addition, the sentence contains parallelism:

can reach up to X [150 miles per hour in speed] and Y [200 feet high]

The portion before the parallelism starts must apply to both the X and Y portions, so the original sentence says:

can reach up to 200 feet high

That might sound kind of clunky and it is: up to and high are redundant.

Okay, answer (A) is incorrect and answer (B) repeats both issues (it neglects to specify speeds of up to 150 and it contains faulty parallelism.).

Check the parallelism in the other choices:

“(C) speeds of up to [150 miles per hour] and [200 feet high]

“(D) [speeds of up to 150 miles per hour] and [heights of up to 200 feet]

“(E) speeds of [up to 150 miles per hour] and [as high as 200 feet]”

In answer (C), the Y portion is the measurement (200 feet), so the X portion should also be the measurement…but it’s nonsensical to say speeds of up to 200 feet high. Likewise, in (E), the Y portion is a prepositional phrase, so it matches the prepositional phrase in the X portion. Now, the sentence says speeds of as high as 200 feet—equally nonsensical.

The only one that makes sense is answer (D): speeds of up to 150 and heights of up to 200.

The correct answer is (D).

You might also have noticed, in the original sentence, that the last underlined word is the verb is. Sentence Correction problems always have at least one difference at the beginning of the underline and at the end, so glance down the end of the choices.

Interesting! Is vs. are. What subject goes with this verb? Here’s the original sentence again:

“Often incorrectly referred to as a tidal wave, a tsunami, a seismic sea wave that can reach up to 150 miles per hour in speed and 200 feet high, is caused by underwater earthquakes or volcanic eruptions.”

The modifiers have been crossed out. The subject is tsunami, a singular noun, so the verb should be the singular is. Answers (C) and (E) are incorrect for this reason.

Key Takeaways: The First Glance in Sentence Correction

(1) Before reading the original sentence, make it a habit to glance at the word or couple of words at the start of the underline and each answer choice. Sometimes, the split will be obvious: an is vs. are split, for example, clearly indicates subject-verb agreement.

(2) Sometimes the split will be less obvious, as with up to vs. speeds of up to. In this case, if the split is fairly easy to remember, just keep the variations in mind as you read the original sentence, so that you can analyze the difference right away. You may see immediately that speeds of up to is more clear, and your knowledge that the sentence is testing this meaning might also alert you to some of the meaning issues introduced by the faulty parallelism.

(3) Making a subject-verb match in the midst of a bunch of modifiers can be tricky. Learn how to strip the modifiers out and take the sentence down to its basic core structure.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

Want to learn more? Read on to part 3.

Manhattan GMAT

Studying for the GMAT? Take our free GMAT practice exam or sign up for a free GMAT trial class running all the time near you, or online. And, be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+, LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter!

Can you Spot the Meaning Error? (part 3)

Welcome to the final installment in a series of three articles about meaning and sentence structure in sentence correction. Our first one tested meaning and also covered issues related to having to break the sentence into chunks. In the second, we talked about how to use that chunk idea to strip the sentence down to the core structure vs. the modifiers.

Welcome to the final installment in a series of three articles about meaning and sentence structure in sentence correction. Our first one tested meaning and also covered issues related to having to break the sentence into chunks. In the second, we talked about how to use that chunk idea to strip the sentence down to the core structure vs. the modifiers.

Today, I’ve got a third GMATPrep® problem for you following some of these same themes (I’m not going to tell you which ones till after you’ve tried the problem!).

* “Today’s technology allows manufacturers to make small cars more fuel-efficient now than at any time in their production history.

“(A) small cars more fuel-efficient now than at any time in their

“(B) small cars that are more fuel-efficient than they were at any time in their

“(C) small cars that are more fuel-efficient than those at any other time in

“(D) more fuel-efficient small cars than those at any other time in their

“(E) more fuel-efficient small cars now than at any time in”

The first glance doesn’t indicate a lot this time. The answers change from small cars to more (fuel-efficient small cars), which isn’t much of a clue. Go ahead and read the original sentence.

What did you think? When I first read it, I shrugged and thought, “That sounds okay.” If you can’t come up with something to tackle from the first glance or the first read-through, then compare answers (A) and (B), looking for differences.

Hmm. I see—do we need to say that are more fuel-efficient? Maybe. Answer (C) uses that same structure. Oh, hey, answer (C) tosses in the word other! I know what they’re doing!

If you’ve seen the word other tested within a comparison before, you may know, too. If not, get ready to make a note. Take a look at these two sentences:

Can you Spot the Meaning Error? (part 2)

Last time, we tried a problem that tested meaning; we also discussed how to compare entire chunks of the answer choices. Today, we’re going to combine those two things into a new skill.

Last time, we tried a problem that tested meaning; we also discussed how to compare entire chunks of the answer choices. Today, we’re going to combine those two things into a new skill.

Try this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams and then we’ll talk about it.

* “The striking differences between the semantic organization of Native American languages and that of European languages, in both grammar and vocabulary, have led scholars to think about the degree to which differences in language may be correlated with nonlinguistic differences.

“(A) that of European languages, in both grammar and vocabulary, have

“(B) that of European languages, including grammar and vocabulary, has

“(C) those of European languages, which include grammar and vocabulary, have

“(D) those of European languages, in grammar as well as vocabulary, has

“(E) those of European languages, both in grammar and vocabulary, has”

At first glance, the underline isn’t super long on this one, Glance down the first word of each answer. What does a split between that and those signify?

Both are pronouns, so they’re referring to something else in the sentence. In addition, one is singular and one is plural, so it will be important to find the antecedent (the word to which the pronoun refers).

Next, read the original sentence. What do you think? It isn’t super long but it still manages to pack in some complexity. Learn how to strip it down and you’ll be prepared for even more complex sentence structures.

My first thought was: okay, now I see why they offered that vs. those. Should the pronoun refer to the plural differences or to the singular organization?

It could be easy to get turned around here, so strip down the sentence structure:

Introducing The Official Guide Companion for Sentence Correction

We are very excited to announce that our new book, The Official Guide Companion for Sentence Correction, will hit bookshelve today, December 3rd!

What is the OGSC (for short)?

It’s one of the best GMAT study guides you could have (if we do say so ourselves)!

Here’s the deal: nearly everyone studies from The Official Guide for GMATÒ Review, 13th Edition (or OG13). This book contains about 900 real GMAT questions that appeared on the exam in the past. OG13 does contain explanations, but those explanations are “textbook” explanations: reading them is like reading a grammar book. The answers are completely accurate but a bit hard to follow if you’re not a grammar teacher (and some of them are hard to follow even when you are a grammar teacher… ahem).

So we decided to remedy that problem by writing our own explanations for every single one of the 159 Sentence Correction problems contained in OG13. We’ll tell you the SC Process for getting through any SC question efficiently and effectively. We’ll also discuss how to eliminate each wrong answer in terms that are easy for students (not just teachers) to understand. The book includes an extra section on sentence structure and a glossary of common grammar terms. Finally, you’ll gain access to our online GMAT Navigator program which lets you track your OG work, time yourself, and view your performance data so that you can better determine your strengths and weaknesses.

Who should use the OGSC?

Are you struggling to improve your SC performance? Do you love studying official problems but hate trying to decipher the sometimes-mystifying official explanations? Do you want to throw your OG13 across the room when you read yet another explanation that says an answer choice is “wordy” or “awkward”?

If something is “awkward,” there is a real reason why—and we explain that specific reason to you so that you can start to pick out similar faulty constructions on other problems in future. (Did you know that, most of the time, “wordy” and “awkward” are code words for an ambiguous or illogical meaning? The OGSC will help you learn how to decipher these for yourself!)

How can I get the most out of the OGSC?

First, read the introduction chapter, where you’ll learn all about how to work through an SC problem in an efficient manner.

Next, if you have already started studying Sentence Correction problems from the OG, begin with the problems that you’ve tried recently. Try to articulate to yourself why each of the four wrong answers is wrong. Try to find all of the errors in each answer (though, on the real test, just one error is enough to eliminate an answer!).

Note: You don’t need to use grammar terminology when you’re trying to articulate why something’s wrong, but do try to go beyond “this one sounds bad.” That’s a good starting point but which part, specifically, sounds bad? What sounds so bad about that part?

Then, check yourself against the explanations. If you didn’t spot a particular error, go back to the problem and ask yourself what clues (in the form of differences in the answer choices) will alert you the next time this particular topic is being tested. If you didn’t know how to handle the issue but now understand from the explanation, make yourself a flashcard to help you remember whatever that is for future. If the explanation seems like Greek to you, then maybe this particular issue is too hard and your take-away is to skip something like this in future and make a guess!

When you’re ready to try new OG problems, make sure to do them under timed conditions (try to average about 1 minute 20 seconds on SC). When you’re done, check the answer. If you guessed, go ahead straight to the explanation. If you got it right, try to articulate why each incorrect answer is wrong, then check the explanation. If you got it wrong, look at the problem again to see whether you might have made a careless mistake. Then go to the explanation.

Where can I get the OGSC?

You can find The Official Guide Companion for Sentence Correction on our website starting today!

Let us know what you think in the Comments section below. Good luck and happy studying!

Sentence Correction: Get the Most Out of Your First Glance

For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been learning the 4-step SC Process. (If you haven’t read that two-part article yet, go do so now!) Also, grab your copy of The Official Guide 13th Edition (OG13); you’re going to need it for the exercises in this article.

For the past couple of weeks, we’ve been learning the 4-step SC Process. (If you haven’t read that two-part article yet, go do so now!) Also, grab your copy of The Official Guide 13th Edition (OG13); you’re going to need it for the exercises in this article.

People often ask what they should check “first” in SC, or in what order they should check various potential grammar problems. It would take too long to check for a laundry list of error types every time, though, so what to do? You take a First Glance: a 2-3 second glance at the screen with the goal of picking up a clue or two about this problem before you even start reading it.

Open up your OG13 to the SC section right now—any page will do—and find a really long underline. Now find a really short one.

How would you react to each of these? Each one has its own hints. Think about this before you keep reading.

A really long underline increases the chances that “global” issues will be tested. These issues include Structure, Meaning, Modifiers, and Parallelism—it’s easier to test all of these issues when the underline contains a majority of the sentence.

A really short underline (around 5-6 words or fewer) should trigger a change in strategy. Instead of reading the original sentence first, compare the answers to see what the differences are. This won’t take long because there aren’t many words to compare! Those differences can give you ideas as to what the sentence is testing.

Either way, you’ve now got some ideas about what might be happening in the sentence before you even read it—and that is the goal of the First Glance.

Read a Couple of Words

Next, we’re going to do a drill. Flip to page 672 (print edition) of OG13 but don’t read anything yet. Also, open up a notebook or a file on your computer to take notes. (Note: I’m starting us on the first page of SC problems because I want to increase the chances that you’ve already done some of these problems in the past. It’s okay if you haven’t done them all yet. You can also switch to a different page if you want, but I’m going to discuss some of these problems below, FYI.)

Start with the first problem on the page. Give yourself a maximum of 5 seconds to glance at that problem. Note the length of the underline. Read the word right before the underline and the first word of the underline, but that’s it! Don’t read the rest of the sentence. Also go and look at the first word of each answer choice. As you do this, takes notes on what you see.

For the next step, you can take all the time you want (but still do not go back and read the full sentence / problem). Ask yourself whether any of that provides any clues. Read more

How To Solve Any Sentence Correction Problem, Part 2

In the first half of this article, we talked about the 5-step process to answer SC problems:

In the first half of this article, we talked about the 5-step process to answer SC problems:

1. Take a First Glance

2. Read the Sentence

3. Find a Starting Point

4. Eliminate Answers

5. Repeat steps 3 and 4

If you haven’t already learned that process, read the first half before continuing with this part.

Drills to Build Skills

How do you learn to do all of this stuff? You’re going to build some skills that will help at each stage of the way. You might already feel comfortable with one or multiple of these skills, so feel free to choose the drills that match your specific needs.

Drill Number 1: First Glance

Open up your Official Guide and find some lower-numbered SC questions that you’ve already tried in the past. Give yourself a few seconds (no more than 5!) to glance at a problem, then look away and say out loud what you noticed in those few seconds.

As you develop your First Glance skills, you can start to read a couple of words: the one right before the underline and the first word of the underline. Do those give you any clues about what might be tested in the problem? For instance, consider this sentence:

Xxx xxxxxx xxxx xx and she xxx xxxxx xxxx xxxx xxx xxx xxxxx.

I can’t know for sure, but I have a strong suspicion that this problem might test parallelism, because the word and falls immediately before the underline. When I read the sentence, I’ll be looking for an X and Y parallelism structure.

At first, you’ll often say something like, “I saw that the underline starts with the word psychologists but I have no idea what that might mean.” (Note: this example is taken from OG13 SC #1!) That’s okay; you’re about to learn. Go try the problem (practicing the rest of the SC process as described in the first half of this article) and ask yourself again afterwards, “So what might I have picked up from that starting clue?”

The word psychologists is followed by a comma… so perhaps something will be going on with modifiers? Or maybe this is a list? The underline is really long as well, which tends to go with modifiers. Now, when you start to read the sentence, you will already be prepared to figure out what’s going on with this word. (In this case, it turns out that psychologists is followed only by modifiers; the original sentence is missing a verb!)

Drill Number 2: Read the Sentence

Take a look at some OG problems you’ve tried before. Read only the original sentence. Then, look away from the book and articulate aloud, in your own words, what you think the sentence is trying to convey. You don’t need to limit yourself to one sentence. You can also glance back at the problem to confirm details.

I want to stress the “out loud” part; you will be able to hear whether the explanation is sufficient. If so, try another problem.

If you’re struggling or unsure, then one of two things is happening. Either you just don’t understand, or the sentence actually doesn’t have a clear meaning and that’s why it’s wrong! Decide which you think it is and then look at the explanation. Does the explanation’s description of the sentence match what you thought—the sentence actually does have a meaning problem? If not, then how does the explanation explain the sentence? That will help you learn how to “read it right” the next time. (If you don’t like the OG explanation, try looking in our GMAT Navigator program.)

Drill Number 3: Find a Starting Point

Once again, open up your OG and look at some problems you have done before. This time, do NOT read the original sentence. Instead, cover it up. Read more

Comparisons in GMATPrep Sentence Correction

I’ve got a fascinating (and infuriating!) GMATPrep problem for you today; this comes from the free problem set included in the new GMATPrep 2.0 version of the software. Try it out (1 minute 15 seconds) and then we’ll talk about it!

* Unlike computer skills or other technical skills, there is a disinclination on the part of many people to recognize the degree to which their analytical skills are weak.

(A) Unlike computer skills or other technical skills, there is a disinclination on the part of many people to recognize the degree to which their analytical skills are weak.

(B) Unlike computer skills or other technical skills, which they admit they lack, many people are disinclined to recognize that their analytical skills are weak.

(C) Unlike computer skills or other technical skills, analytical skills bring out a disinclination in many people to recognize that they are weak to a degree.

(D) Many people, willing to admit that they lack computer skills or other technical skills, are disinclined to recognize that their analytical skills are weak.

(E) Many people have a disinclination to recognize the weakness of their analytical skills while willing to admit their lack of computer skills or other technical skills.

I chose this problem because I thought the official explanation fell short; specifically, there are multiple declarations that something is wordy or awkward. While I agree with those characterizations, they aren’t particularly useful as teaching tools “ how can we tell that something is wordy or awkward? There isn’t an absolute way to rule; it’s a judgment call.

I chose this problem because I thought the official explanation fell short; specifically, there are multiple declarations that something is wordy or awkward. While I agree with those characterizations, they aren’t particularly useful as teaching tools “ how can we tell that something is wordy or awkward? There isn’t an absolute way to rule; it’s a judgment call.

Now, I can understand why whoever wrote this explanation struggled to do so; this is an extremely difficult problem to explain. And that’s exactly why I wanted to have a crack at it “ I like a challenge. : )

Okay, let’s talk about the problem. My first reaction to the original sentence was: nope, that’s definitely wrong. When you think that, your next thought should be, Why? Which part, specifically? This allows you to know that you have a valid reason for eliminating an answer and it also allows you to figure out what you should examine in other answers.

Before you read my next paragraph, answer that question for yourself. What, specifically, doesn’t sound good or doesn’t work in the original sentence?

Read more

Modifier Madness: Breaking Down a GMATPrep Sentence Correction Problem

This week, we’re going to analyze a particularly tough GMATPrepSentence Correction question.

First, set your timer for 1 minute and 15 seconds and try the problem!

Research has shown that when speaking, individuals who have been blind from birth and have thus never seen anyone gesture nonetheless make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way as sighted people do, and that they will gesture even when conversing with another blind person.

A) have thus never seen anyone gesture nonetheless make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way as sighted people do, and that

B) have thus never seen anyone gesture but nonetheless make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way that sighted people do, and

C) have thus never seen anyone gesture, that they nonetheless make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way as sighted people do, and

D) thus they have never seen anyone gesture, but nonetheless they make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way that sighted people do, and that

E) thus they have never seen anyone gesture nonetheless make hand motions just as frequently and in the same way that sighted people do, and

Okay, have you got your answer? Now, let’s dive into this thing! What did you think when you read the original sentence?

This is a very tough problem; when I read the sentence the first time, I actually had to stop and try to strip the sentence down to its basic core, then figure out how the modifiers fit. Until I did that, I couldn’t go any further.

Read more