Want a Better GMAT Score? Go to Sleep!

This is going to be a short post. It will also possibly have the biggest impact on your study of anything you do all day (or all month!).

This is going to be a short post. It will also possibly have the biggest impact on your study of anything you do all day (or all month!).

When people ramp up to study for the GMAT, they typically find the time to study by cutting down on other activities—no more Thursday night happy hour with the gang or Sunday brunch with the family until the test is over.

There are two activities, though, that you should never cut—and, unfortunately, I talk to students every day who do cut these two activities. I hear this so much that I abandoned what I was going to cover today and wrote this instead. We’re not going to cover any problems or discuss specific test strategies in this article. We’re going to discuss something infinitely more important!

#1: You must get a full night’s sleep

Period. Never cut your sleep in order to study for this test. NEVER.

Your brain does not work as well when trying to function on less sleep than it needs. You know this already. Think back to those times that you pulled an all-nighter to study for a final or get a client presentation out the door. You may have felt as though you were flying high in the moment, adrenaline coursing through your veins. Afterwards, though, your brain felt fuzzy and slow. Worse, you don’t really have great memories of exactly what you did—maybe you did okay on the test that morning, but afterwards, it was as though you’d never studied the material at all.

There are two broad (and very negative) symptoms of this mental fatigue that you need to avoid when studying for the GMAT (and doing other mentally-taxing things in life). First, when you are mentally fatigued, you can’t function as well as normal in the moment. You’re going to make more careless mistakes and you’re just going to think more slowly and painfully than usual.

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (part 3)

Welcome to our third and final installment dedicated to those pesky maximize / minimize quant problems. If you haven’t yet reviewed the earlier installments, start with part 1 and work your way back up to this post.

I’d originally intended to do just a two-part series, but I found another GMATPrep® problem (from the free tests) covering this topic, so here you go:

“A set of 15 different integers has a median of 25 and a range of 25. What is the greatest possible integer that could be in this set?

“(A) 32

“(B) 37

“(C) 40

“(D) 43

“(E) 50”

Here’s the general process for answering quant questions—a process designed to make sure that you understand what’s going on and come up with the best plan before you dive in and solve:

Fifteen integers…that’s a little annoying because I don’t literally want to draw 15 blanks for 15 numbers. How can I shortcut this while still making sure that I’m not missing anything or causing myself to make a careless mistake?

Hmm. I could just work backwards: start from the answers and see what works. In this case, I’d want to start with answer (E), 50, since the problem asks for the greatest possible integer.

Read more

How to Infer on the GMAT

We’re going to kill two birds with one stone in this week’s article.

We’re going to kill two birds with one stone in this week’s article.

Inference questions pop up on both Critical Reasoning (CR) and Reading Comprehension (RC), so you definitely want to master these. Good news: the kind of thinking the test-writers want is the same for both question types. Learn how to do Inference questions on one type and you’ll know what you need to do for the other!

That’s actually only one bird. Here’s the second: both CR and RC can give you science-based text, and that science-y text can get pretty confusing. How can you avoid getting sucked into the technical detail, yet still be able to answer the question asked? Read on.

Try this GMATPrep® CR problem out (it’s from the free practice tests) and then we’ll talk about it. Give yourself about 2 minutes (though it’s okay to stretch to 2.5 minutes on a CR as long as you are making progress.)

“Increases in the level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in the human bloodstream lower bloodstream cholesterol levels by increasing the body’s capacity to rid itself of excess cholesterol. Levels of HDL in the bloodstream of some individuals are significantly increased by a program of regular exercise and weight reduction.

“Which of the following can be correctly inferred from the statements above?

“(A) Individuals who are underweight do not run any risk of developing high levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream.

“(B) Individuals who do not exercise regularly have a high risk of developing high levels of cholesterol in the bloodstream late in life.

“(C) Exercise and weight reduction are the most effective methods of lowering bloodstream cholesterol levels in humans.

“(D) A program of regular exercise and weight reduction lowers cholesterol levels in the bloodstream of some individuals.

“(E) Only regular exercise is necessary to decrease cholesterol levels in the bloodstream of individuals of average weight.”

Got an answer? (If not, pick one anyway. Pretend it’s the real test and just make a guess.) Before we dive into the solution, let’s talk a little bit about what Inference questions are asking us to do.

Inference questions are sometimes also called Draw a Conclusion questions. I don’t like that title, though, because it can be misleading. Think about a typical CR argument: they usually include a conclusion that is…well…not a solid conclusion. There are holes in the argument, and then they ask you to Strengthen it or Weaken it or something like that.

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (Part 2)

Last time, we discussed two GMATPrep® problems that simultaneously tested statistics and the concept of maximizing or minimizing a value. The GMAT could ask you to maximize or minimize just about anything, so the latter skill crosses many topics. Learn how to handle the nuances on these statistics problems and you’ll learn how to handle any max/min problem they might throw at you.

Last time, we discussed two GMATPrep® problems that simultaneously tested statistics and the concept of maximizing or minimizing a value. The GMAT could ask you to maximize or minimize just about anything, so the latter skill crosses many topics. Learn how to handle the nuances on these statistics problems and you’ll learn how to handle any max/min problem they might throw at you.

Feel comfortable with the two problems from the first part of this article? Then let’s kick it up a notch! The problem below was written by us (Manhattan Prep) and it’s complicated—possibly harder than anything you’ll see on the real GMAT. This problem, then, is for those who are looking for a really high quant score—or who subscribe to the philosophy that mastery includes trying stuff that’s harder than what you might see on the real test, so that you’re ready for anything.

Ready? Here you go:

“Both the average (arithmetic mean) and the median of a set of 7 numbers equal 20. If the smallest number in the set is 5 less than half the largest number, what is the largest possible number in the set?

“(A) 40

“(B) 38

“(C) 33

“(D) 32

“(E) 30”

Out of the letters A through E, which one is your favorite?

You may be thinking, “Huh? What a weird question. I don’t have a favorite.”

I don’t have one in the real world either, but I do for the GMAT, and you should, too. When you get stuck, you’re going to need to be able to let go, guess, and move on. If you haven’t been able to narrow down the answers at all, then you’ll have to make a random guess—in which case, you want to have your favorite letter ready to go.

If you have to think about what your favorite letter is, then you don’t have one yet. Pick it right now.

I’m serious. I’m not going to continue until you pick your favorite letter. Got it?

From now on, when you realize that you’re lost and you need to let go, pick your favorite letter immediately and move on. Don’t even think about it.

Read more

Tackling Max/Min Statistics on the GMAT (Part 1)

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

Blast from the past! I first discussed the problems in this series way back in 2009. I’m reviving the series now because too many people just aren’t comfortable handling the weird maximize / minimize problem variations that the GMAT sometimes tosses at us.

In this installment, we’re going to tackle two GMATPrep® questions. Next time, I’ll give you a super hard one from our own archives—just to see whether you learned the material as well as you thought you did. 🙂

Here’s your first GMATPrep problem. Go for it!

“*Three boxes of supplies have an average (arithmetic mean) weight of 7 kilograms and a median weight of 9 kilograms. What is the maximum possible weight, in kilograms, of the lightest box?

“(A) 1

“(B) 2

“(C) 3

“(D) 4

“(E) 5”

When you see the word maximum (or a synonym), sit up and take notice. This one word is going to be the determining factor in setting up this problem efficiently right from the beginning. (The word minimum or a synonym would also apply.)

When you’re asked to maximize (or minimize) one thing, you are going to have one or more decision points throughout the problem in which you are going to have to maximize or minimize some other variables. Good decisions at these points will ultimately lead to the desired maximum (or minimum) quantity.

This time, they want to maximize the lightest box. Step back from the problem a sec and picture three boxes sitting in front of you. You’re about to ship them off to a friend. Wrap your head around the dilemma: if you want to maximize the lightest box, what should you do to the other two boxes?

Note also that the problem provides some constraints. There are three boxes and the median weight is 9 kg. No variability there: the middle box must weigh 9 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

The three items also have an average weight of 7. The total weight, then, must be (7)(3) = 21 kg.

Subtract the middle box from the total to get the combined weight of the heaviest and lightest boxes: 21 – 9 = 12 kg.

The heaviest box has to be equal to or greater than 9 (because it is to the right of the median). Likewise, the lightest box has to be equal to or smaller than 9. In order to maximize the weight of the lightest box, what should you do to the heaviest box?

Minimize the weight of the heaviest box in order to maximize the weight of the lightest box. The smallest possible weight for the heaviest box is 9.

If the heaviest box is minimized to 9, and the heaviest and lightest must add up to 12, then the maximum weight for the lightest box is 3.

The correct answer is (C).

Make sense? If you’ve got it, try this harder GMATPrep problem. Set your timer for 2 minutes!

“*A certain city with a population of 132,000 is to be divided into 11 voting districts, and no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district. What is the minimum possible population that the least populated district could have?

“(A) 10,700

“(B) 10,800

“(C) 10,900

“(D) 11,000

“(E) 11,100”

Hmm. There are 11 voting districts, each with some number of people. We’re asked to find the minimum possible population in the least populated district—that is, the smallest population that any one district could possibly have.

Let’s say that District 1 has the minimum population. Because all 11 districts have to add up to 132,000 people, you’d need to maximize the population in Districts 2 through 10. How? Now, you need more information from the problem:

“no district is to have a population that is more than 10 percent greater than the population of any other district”

So, if the smallest district has 100 people, then the largest district could have up to 10% more, or 110 people, but it can’t have any more than that. If the smallest district has 500 people, then the largest district could have up to 550 people but that’s it.

How can you use that to figure out how to split up the 132,000 people?

In the given problem, the number of people in the smallest district is unknown, so let’s call that x. If the smallest district is x, then calculate 10% and add that figure to x: x + 0.1x = 1.1x. The largest district could be 1.1x but can’t be any larger than that.

Since you need to maximize the 10 remaining districts, set all 10 districts equal to 1.1x. As a result, there are (1.1x)(10) = 11x people in the 10 maximized districts (Districts 2 through 10), as well as the original x people in the minimized district (District 1).

The problem indicated that all 11 districts add up to 132,000, so write that out mathematically:

11x + x = 132,000

12x = 132,000

x = 11,000

The correct answer is (D).

Practice this process with any max/min problems you’ve seen recently and join me next time, when we’ll tackle a super hard problem.

Key Takeaways for Max/Min Problems:

(1) Figure out what variables are “in play”: what can you manipulate in the problem? Some of those variables will need to be maximized and some minimized in order to get to the desired answer. Figure out which is which at each step along the way.

(2) Did you make a mistake—maximize when you should have minimized or vice versa? Go through the logic again, step by step, to figure out where you were led astray and why you should have done the opposite of what you did. (This is a good process in general whenever you make a mistake: figure out why you made the mistake you made, as well as how to do the work correctly next time.)

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 4)

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

It’s here at last: the fourth and final installment of our series on core sentence structure! I recommend reading all of the installments in order, starting with part 1.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams.

* “The greatest road system built in the Americas prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending from northern Ecuador through Peru to southern Chile.

“(A) Columbus was the Incan highway, which, over 2,500 miles long and extending

“(B) Columbus was the Incan highway, over 2,500 miles in length, and extended

“(C) Columbus, the Incan highway, which was over 2,500 miles in length and extended

“(D) Columbus, the Incan highway, being over 2,500 miles in length, was extended

“(E) Columbus, the Incan highway, was over 2,500 miles long, extending”

The First Glance in this question is similar to the one from the second problem in the series. Here, the first two answers start with a noun and verb, but the next three insert a comma after the subject. Once again, this is a clue to check the core subject-verb sentence structure.

First, strip down the original sentence:

Here’s the core:

The greatest road system was the Incan highway.

(Technically, greatest is a modifier, but I’m leaving it in because it conveys important meaning. We’re not just talking about any road system. We’re talking about the greatest one in a certain era.)

The noun at the beginning of the underline, Columbus, is not the subject of the sentence but the verb was does turn out to be the main verb in the sentence. The First Glance revealed that some answers removed that verb, so check the remaining cores.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(C) The greatest road system.

“(D) The greatest road system was extended from Ecuador to Chile.

“(E) The greatest road system was over 2,500 miles long.”

Answer (C) is a sentence fragment; it doesn’t contain a main verb. The other choices do contain valid core sentences, though answers (B) and (D) have funny meanings. Let’s tackle (B) first.

“(B) The greatest road system was the Incan highway and extended from Ecuador to Chile.

When two parts of a sentence are connected by the word and, those two parallel pieces of information are not required to have a direct connection:

Yesterday, I worked for 8 hours and had dinner with my family.

Those things did not happen simultaneously. One did not lead to the other. They are both things that I did yesterday, but other than that, they don’t have anything to do with each other.

In the Columbus sentence, though, it doesn’t make sense for the two pieces of information to be separated in this way. The road system was the greatest system built to that point in time because it was so long. The fact that it extended across all of these countries is part of the point. As a result, we don’t want to present these as separate facts that have nothing to do with each other. Eliminate answer (B).

Read more

What is the GMAT? An Introduction to the GMAT Exam

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

The Graduate Management Admission Test, better known as the GMAT®, is a standardized test used in the admissions process for business school and other specialized master’s programs. The exam measures certain skills that business schools care about, most notably Executive Reasoning skills. It does not test any specific business knowledge. Read on for an introduction to the GMAT. Read more

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 3)

Welcome to the third installment of our Core Sentence series. In part 1, we began learning how to strip an SC sentence (or any sentence!) down to the core sentence structure. In part 2, we took a look at a compound sentence structure.

Welcome to the third installment of our Core Sentence series. In part 1, we began learning how to strip an SC sentence (or any sentence!) down to the core sentence structure. In part 2, we took a look at a compound sentence structure.

Today, we’re going to look at yet another interesting sentence structure that is commonly used on the GMAT.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. (Note: as in the previous installments, I’m going to discuss aspects of our SC Process; if you haven’t learned it already, read about it before doing this problem.)

* “Many financial experts believe that policy makers at the Federal Reserve, now viewing the economy as balanced between moderate growth and low inflation, are almost certain to leave interest rates unchanged for the foreseeable future.

“(A) Reserve, now viewing the economy as balanced between moderate growth and low inflation, are

“(B) Reserve, now viewing the economy to be balanced between that of moderate growth and low inflation and are

“(C) Reserve who, now viewing the economy as balanced between moderate growth and low inflation, are

“(D) Reserve, who now view the economy to be balanced between that of moderate growth and low inflation, will be

“(E) Reserve, which now views the economy to be balanced between moderate growth and low inflation, is”

The First Glance didn’t tell me a lot on this one. In each case, there appears to be some kind of modifier going on, signaled either by the who / which language or by the comma, but I don’t have a good idea of what’s being tested. Time to read the sentence.

I don’t know about you, but the original sentence really doesn’t sound good to me. The difficulty, though, is that I don’t know exactly why. I just find myself thinking, “Ugh, I wouldn’t say it that way.”

Specifically, I don’t like the “now viewing” after the comma…but when I examined it a second time, I couldn’t find an actual error. That’s a good clue to me that I need to leave the answer in; they’re just trying to fool my ear (and almost succeeding!).

Because I’m not certain what to examine and because I know that there may be something going on with modifiers, I’m going to strip the original sentence down to the core:

Here’s the core:

Many experts believe that policy makers are almost certain to leave interest rates unchanged.

This sentence uses what we call a “Subject-Verb-THAT” structure. When you see the word that immediately after a verb, expect another subject and verb (and possibly object) to come after. The full core will be Subject-Verb-THAT-Subject-Verb(-Object).

Back to the problem: notice where the underline falls. The Subject-Verb-THAT-Subject part is not underlined, but the second verb is, and it’s the last underlined word. Check the core sentence with the different options in the answers:

Many experts believe that policy makers __________ almost certain to leave rates unchanged.

(A) Many experts believe that policy makers are almost certain to leave rates unchanged.

(B) Many experts believe that policy makers and are almost certain to leave rates unchanged.

(C) Many experts believe that policy makers.

(D) Many experts believe that policy makers will be almost certain to leave rates unchanged.

(E) Many experts believe that policy makers is almost certain to leave rates unchanged.

Excellent! First, answer (E) is wrong because it uses a singular verb to match with the plural policy makers.

Next, notice that answer (B) tosses the conjunction and into the mix. A sentence can have two verbs, in which case you could connect them with an and, but this answer just tosses in a random and between the subject and the verb. Answer (B) is also incorrect.

Answer (C) is tricky! At first, it might look like the core is the same as answer (A)’s core. It’s not. Notice the lack of a comma before the word who. Take a look at this example:

The cat thought that the dog who lived next door was really annoying.

What’s the core sentence here? This still has a subject-verb-THAT-subject-verb(-object) set-up. It also has a modifier that contains its own verb—but this verb is not part of the core sentence:

The cat thought that the dog [who lived next door] was really annoying.

Answer (C) has this same structure:

Many experts believe that policy makers [who are almost certain to leave rates unchanged]…

Where’s the main verb that goes with policy makers? It isn’t there at all. Answer (C) is a sentence fragment.

We’re down to answers (A) and (D). Both cores are solid, so we’ll have to dig a little deeper. So far, we’ve been ignoring the modifier in the middle of the sentence. Let’s take a look; compare the two answers directly:

“(A) Reserve, now viewing the economy as balanced between moderate growth and low inflation, are

“(D) Reserve, who now view the economy to be balanced between that of moderate growth and low inflation, will be”

Probably the most obvious difference is are vs. will be. I don’t like this one though because I think either tense can logically finish the sentence. I’m going to look for something else.

There are two other big differences. First, there’s an idiom. Is it view as or view to be? If you’re not sure, there’s also a comparison issue. Is the economy balanced between growth and inflation? Or between that of growth and inflation?

The that of structure should be referring to another noun somewhere else: She likes her brother’s house more than she likes that of her sister. In this case, that of refers to house.

What does that of refer to in answer (D)?

I’m not really sure. The economy? The Federal Reserve? These don’t make sense. The two things that are balanced are, in fact, the growth and the inflation; that of is unnecessary. Answer (D) is incorrect.

The correct answer is (A).

The correct idiom is view as, so answers (B), (D), and (E) are all incorrect based on the idiom.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core

(1) When you see the word that immediately following a verb, then you have a Subject-Verb-THAT-Subject-Verb(-Object) structure. Check the core sentence to make sure that all of the necessary pieces are present. Also make sure, as always, that the subjects and verbs match.

(2) If you still have two or more answers left after dealing with the core sentence, then check any modifiers. The two main modifier issues are bad placement (which makes them seem to be pointing to the wrong thing) or meaning issues. In this case, the modifier tossed in a couple of extraneous words that messed up the meaning of the between X and Y idiom.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 2)

Welcome to the second installment of our Core Sentence series; if you haven’t yet read Part 1, do so now before continuing with this segment. How has your practice been going? It’s hard to develop the ability to “grey out” parts of the sentence in your mind. Did you find that you were able to do so without writing anything down? Or did you find that the technique solidified better when you did write out the core sentence?

Welcome to the second installment of our Core Sentence series; if you haven’t yet read Part 1, do so now before continuing with this segment. How has your practice been going? It’s hard to develop the ability to “grey out” parts of the sentence in your mind. Did you find that you were able to do so without writing anything down? Or did you find that the technique solidified better when you did write out the core sentence?

Most people do have to start, in practice, by writing out the core. The goal is to be able to do everything (or almost everything) in your head by the time the real test rolls around.

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams; give yourself about 1 minute 20 seconds. (You can always choose to spend a little longer, since that time is an average, not a limit; more than about 20-30 seconds longer, though, typically just indicates that you’ve gotten stuck. At that point, guess from among the remaining answers and move on.)

* “Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he quickly built his own device from an organ pipe and spectacle lenses.

“(A) Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument having been made,

“(C) Galileo, even though he had not invented the telescope, on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(D) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made,

“(E) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument being made, he”

The First Glance shows a possible sentence structure issue: The first two start with a noun and verb, while the third tosses in a comma after that subject. I’m definitely going to need to check for that verb later!

The final two start with even though, which signals a clause, but a dependent one. That means I’ll have to make sure there’s an independent clause (complete sentence) somewhere later on.

Time to read the original sentence. It’s decently complex. What’s the core sentence?

Here’s the core:

Galileo did not invent the telescope, but he built his own device.

This actually consists of two complete sentences connected by a “comma and” conjunction. There’s nothing wrong with the core on this one. Now, you have a choice. You can check the modifiers in the original sentence (and, indeed, if you did spot any problems, you’d want to go deal with those right away). If not, though, then start with those potential structure issues spotted during the first glance.

Strip out the core for the other four answers:

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but quickly built his own device.

“(C) Galileo he quickly built his own device.

“(D) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, quickly built his own device.

“(E) Even though Galileo did not invent the telescope, but he quickly built his own device.”

Excellent! Now we have something to work with! Answer (C) doubles the subject; we don’t need to say both Galileo and he.

Answers (D) and (E) both start with even though, creating a dependent clause. Answer (D) doesn’t have an independent clause later because the part after the comma is missing the subject he.

Note: answer (B) might appear to have the same problem as (D), but the structures are not the same. Answer (B) begins with an independent clause. In this case, it’s okay to say the subject only once at the beginning and then attach two different verbs (had not invented and built) to that subject. (You may still think this one sounds funny. More on this below.)

Answer (E) does have an independent clause later, but there’s a meaning problem. The word but already indicates a contrast. Using both even though and but to connect the two parts of the sentence is redundant.

Okay, (C), (D) and (E) have all been eliminated. Now, compare (A) and (B) directly.

“(A) Galileo did not invent the telescope, but on hearing, in 1609, that such an optical instrument had been made, he

“(B) Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard, in 1609, of such an optical instrument having been made,”

There are a couple of different ways to tackle this, but I’m going to stick to the sentence structure route, since that’s our theme today. Answer (B) does have one more clause in it, though it’s a dependent clause:

“Galileo had not invented the telescope, but when he heard of such an optical instrument having been made, quickly built his own device.”

Now, we do have a problem with the structure! If that intervening dependent clause weren’t there at all, then the core could have been okay: Subject verb, but verb. Technically, you wouldn’t want a comma there, but that’s really the only small issue.

When, however, you introduce a dependent clause in the middle, you can’t carry that original subject, Galileo, all the way over to the second verb at the end. Instead, as with answer (D), you need a complete sentence after the dependent clause, something like:

Galileo did not invent the telescope, but when he heard that one had been made, HE quickly built his own device.

Answer (B) is also incorrect.

The correct answer is (A).

You’re halfway through! Join me next time, when we’ll take a look at another type of complex sentence structure used commonly on the GMAT.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core, part 2

(1) In the Galileo problem, only the correct answer contains a “legal” core sentence. Though there are other ways to eliminate answers on this problem, you still need to learn how to deal with structure. GMAC (the organization that makes the GMAT) has said for several years now that they are including more SC problems in which you really do have to understand the underlying meaning or sentence structure in order to get yourself all the way down to the right answer.

(2) Complex sentence structures can come in many flavors. One of the most common is the compound sentence, which consists of at least two complete sentences connected by a “comma + conjunction” or a semi-colon. The comma conjunction” structure will use the FANBOYS (For And Nor But Or Yes So). You can learn more about the FANBOYS in chapter 3 (Sentence Structure) of our 6th edition Sentence Correction Strategy Guide.

(3) A sentence can also contain dependent clauses (and the complicated sentences we see on the GMAT often do). Common words that signal a dependent clause include although, if, since, that, unless, when, and while. You can learn more about these in chapter 4 (Modifiers) of our 6ED SC guide.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

GMAT Sentence Correction: How To Find the Core Sentence (Part 1)

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

Recently, I was discussing sentence structure with one of my classes and we practiced a crucial but difficult GMAT skill: how to strip an SC sentence to its core components. Multiple OG problems can be solved just by eliminating faulty sentence cores—and the real GMAT is testing this skill today more than we see in the published materials.

So I’m going to write a series of articles on just this topic; welcome to part 1 (and props to my Wednesday evening GMAT Fall AA class for inspiring this series!).

Try out this GMATPrep® problem from the free exams. (Note: in the solution, I’m going to discuss aspects of our SC Process; if you haven’t learned it already, go read about it right now, then come back and try this problem.)

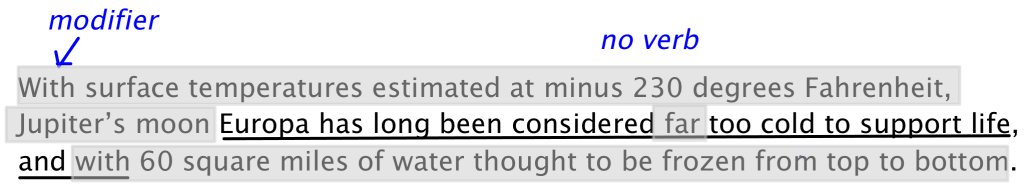

* “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit, Jupiter’s moon Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.

“(A) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, and with

“(B) Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life, its

“(C) Europa has long been considered as far too cold to support life and has

“(D) Europa, long considered as far too cold to support life, and its

“(E) Europa, long considered to be far too cold to support life, and to have”

The First Glance does help on this one, but only if you have studied sentence structure explicitly. Before I did so, I used to think: “Oh, they started with Europa because they added a comma in some answers, but that doesn’t really tell me anything.”

But I’ve learned better! What is that comma replacing? Check it out: the first three answers all have a verb following Europa. The final two don’t; that is, the verb disappears. That immediately makes me suspect sentence structure, because a sentence does have to have a verb. If you remove the main verb from one location, you have to put one in someplace else. I’ll be watching out for that when I read the sentence.

And now it’s time to do just that. As I read the sentence, I strip it down to what we call the “sentence core” in my mind. It took me a long time to develop this skill. I’ll show you the result, first, and then I’ll tell you how I learned to do it.

The “sentence core” refers to the stuff that has to be there in order to have a complete sentence. Everything else is “extra”: it may be important later, but right now, I’m ignoring it.

I greyed out the portions that are not part of the core. How does the sentence look to you?

Notice something weird: I didn’t just strip it down to a completely correct sentence. There’s something wrong with the core. In other words, the goal is not to create a correct sentence; rather, you’re using certain rules to strip to the core even when that core is incorrect.

Using this skill requires you to develop two abilities: the ability to tell what is core vs. extra and the ability to keep things that are wrong, despite the fact that they’ll make your core sound funny. The core of the sentence above is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

Clearly, that’s not a good sentence! So why did I strip out what I stripped out, and yet leave that “comma and” in there? Here was my thought process:

| Text of sentence | My thoughts: |

| “With…” | Preposition. Introduces a modifier. Can’t be the core. |

| “With surface temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit,” | Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new noun modifier. Nothing here is a subject or main verb. * |

| “Jupiter’s moon Europa” | The main noun is Europa; ignore the earlier words. |

| “Europa has long been considered far too cold to support life,” | That’s a complete sentence. Yay. |

| “, and” | A complete sentence followed by “comma and”? I’m expecting another complete sentence to follow. ** |

| “with 60 square miles of water thought to be frozen from top to bottom.” | Same deal as the beginning of the sentence! Each word I’ve italicized introduces a new modifier. Nothing here that can function as a subject or main verb. |

* Why isn’t estimated a verb?

Estimated is a past participle and can be part of a verb form, but you can’t say “Temperatures estimated at minus 230 degrees Fahrenheit.” You’d have to say “Temperatures are estimated at…” (Note: you could say “She estimated her commute to be 45 minutes from door to door.” In other words, estimated by itself can be the main verb of a sentence. In my example, though, the subject is actually doing the estimating. In the GMATPrep problem above, the temperatures can’t estimate anything!)

** Why is it that I expected another complete sentence to follow the “comma and”?

The word and is a parallelism marker; it signals that two parts of the sentence need to be made parallel. When you have one complete sentence, and you follow that with “comma and,” you need to set up another complete sentence to be parallel to that first complete sentence.

For example:

She studied all day, and she went to dinner with friends that night.

The portion before the and is a complete sentence, as is the portion after the and.

(Note: the word and can connect other things besides two complete sentences. It can connect other segments of a sentence as well, such as: She likes to eat pizza, pasta, and steak. In this case, although there is a “comma and” in the sentence, the part before the comma is not a complete sentence by itself. Rather, it is the start of a list.)

Okay, so my core is:

Europa has long been considered too cold to support life, and.

And that’s incorrect. Eliminate answer (A). Either that and needs to go away or, if it stays, I need to have a second complete sentence. Since you know the sentence core is at issue here, check the cores using the other answer choices:

Here are the cores written out:

“(B) Europa has long been considered too cold to support life.

“(C) Europa has long been considered as too cold to support life and has 60 square miles of water.

“(D) Europa and its 60 square miles of water.

“(E) Europa.”

(On the real test, you wouldn’t have time to write that out, but you may want to in practice in order to build expertise with this technique.)

Answers (D) and (E) don’t even have main verbs! Eliminate both. Answers (B) and (C) both contain complete sentences, but there’s something else wrong with one of them. Did you spot it?

The correct idiom is consider X Y: I consider her intelligent. There are some rare circumstances in which you can use consider as, but on the GMAT, go with consider X Y. Answers (C), (D), and (E) all use incorrect forms of the idiom.

Answer (C) also loses some meaning. The second piece of information, about the water, is meant to emphasize the fact that the moon is very cold. When you separate the two pieces of information with an and, however, they appear to be unrelated (except that they’re both facts about Europa): the moon is too cold to support life and, by the way, it also has a lot of frozen water. Still, that’s something of a judgment call; the idiom is definitive.

The correct answer is (B).

Go get some practice with this and join me next time, when we’ll try another GMATPrep problem and talk about some additional aspects of this technique.

Key Takeaways: Strip the sentence to the Core

(1) Generally, this is a process of elimination: you’re removing the things that cannot be part of the core sentence. With rare exceptions, prepositional phrases typically aren’t part of the core. I left the prepositional phrase of water in answers (C) and (D) because 60 square miles by itself doesn’t make any sense. In any case, prepositional phrases never contain the subject of the sentence.

(2) Other non-core-sentence clues: phrases or clauses set off by two commas, relative pronouns such as which and who, comma + -ed or comma + ing modifiers, -ed or –ing words that cannot function as the main verb (try them in a simple sentence with the same subject from the SC problem, as I did with temperatures estimated…)

(3) A complete sentence on the GMAT must have a subject and a working verb, at a minimum. You may have multiple subjects or working verbs. You could also have two complete sentences connected by a comma and conjunction (such as comma and) or a semi-colon. We’ll talk about some additional complete sentence structures next time.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.