What’s the deal with Integrated Reasoning?

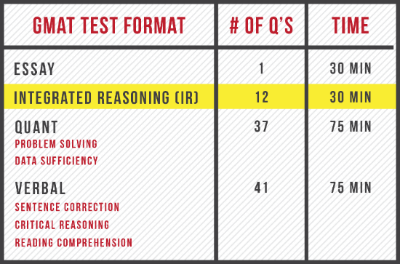

Integrated Reasoning, the newest addition to the GMAT, was added to the GMAT in response to real skills employers are looking for in new hires – namely, the ability to analyze information presented in multiple ways – in order to succeed in today’s data-driven workplace. Sounds tough, right? The good news is that Integrated Reasoning can be learned.

And we’ve created a new tool to teach it—available for free for a limited time only!

The complete GMAT INTERACT platform (coming in June!) will teach every section of the GMAT, but you can get started on the IR section right now, for free. It won’t be available for free forever, though, so be sure to sign up before it’s too late!

Are you ready to learn Integrated Reasoning? Try GMAT INTERACT for Integrated Reasoning for free here.

Open House – Earn $100/hr Teaching with Manhattan Prep

//youtu.be/fi1Do93UizU

Please join us for an exciting, online open house to learn about the rewarding teaching opportunities with Manhattan Prep.

We are seeking expert teachers throughout the US who have proven their mastery of the GMAT, GRE or LSAT and who can engage students of all ability levels. Our instructors teach in classroom and one-on-one settings, both in-person and online. We provide extensive, paid training and a full suite of print and digital instructional materials. Moreover, we encourage the development and expression of unique teaching styles..

All Manhattan Prep instructors earn $100/hour for teaching and tutoring – up to four times the industry standard. These are part-time positions with flexible hours. Many of our instructors maintain full-time positions, engage in entrepreneurial endeavors, or pursue advanced degrees concurrently while teaching for Manhattan Prep. (To learn more about our exceptional instructors, read their bios or view this short video.

Learn about how to transform your passion for teaching into a lucrative and fulfilling part-time career by joining us for this Online Open House event!

To attend this free event, please select from one of the following online events and follow the on-screen instructions:

About Manhattan Prep

Manhattan Prep is a premier test-preparation company serving students and young professionals studying for the GMAT (business school), LSAT (law school), GRE (master’s and PhD programs), and SAT (undergraduate programs). We are the leading provider of GMAT prep in the world.

Manhattan Prep conducts in-person classes and private instruction across the United States, Canada, and England. Our online courses are available worldwide, and our acclaimed Strategy Guides are available at Barnes & Noble and Amazon. In addition, Manhattan Prep serves an impressive roster of corporate clients, including many Fortune 500 companies. For more information, visit www.manhattanprep.com.

The 4 GMAT Math Strategies Everyone Must Master: Testing Cases Redux

A while back, we talked about the 4 GMAT math strategies that everyone needs to master. Today, I’ve got some additional practice for you with regard to one of those strategies: Testing Cases.

A while back, we talked about the 4 GMAT math strategies that everyone needs to master. Today, I’ve got some additional practice for you with regard to one of those strategies: Testing Cases.

Try this GMATPrep® problem:

* ” If xy + z = x(y + z), which of the following must be true?

“(A) x = 0 and z = 0

“(B) x = 1 and y = 1

“(C) y = 1 and z = 0

“(D) x = 1 or y = 0

“(E) x = 1 or z = 0

How did it go?

This question is called a “theory” question: there are just variables, no real numbers, and the answer depends on some characteristic of a category of numbers, not a specific number or set of numbers. Problem solving theory questions also usually ask what must or could be true (or what must not be true). When we have these kinds of questions, we can use theory to solve—but that can get very confusing very quickly. Testing real numbers to “prove” the theory to yourself will make the work easier.

The question stem contains a given equation:

xy + z = x(y + z)

Whenever the problem gives you a complicated equation, make your life easier: try to simplify the equation before you do any more work.

xy + z = x(y + z)

xy + z = xy + xz

z = xz

Very interesting! The y term subtracts completely out of the equation. What is the significance of that piece of info?

Nothing absolutely has to be true about the variable y. Glance at your answers. You can cross off (B), (C), and (D) right now!

Next, notice something. I stopped at z = xz. I didn’t divide both sides by z. Why?

In general, never divide by a variable unless you know that the variable does not equal zero. Dividing by zero is an “illegal” move in algebra—and it will cause you to lose a possible solution to the equation, increasing your chances of answering the problem incorrectly.

The best way to finish off this problem is to test possible cases. Notice a couple of things about the answers. First, they give you very specific possibilities to test; you don’t even have to come up with your own numbers to try. Second, answer (A) says that both pieces must be true (“and”) while answer (E) says “or.” Keep that in mind while working through the rest of the problem.

z = xz

Let’s see. z = 0 would make this equation true, so that is one possibility. This shows up in both remaining answers.

If x = 0, then the right-hand side would become 0. In that case, z would also have to be 0 in order for the equation to be true. That matches answer (A).

If x = 1, then it doesn’t matter what z is; the equation will still be true. That matches answer (E).

Wait a second—what’s going on? Both answers can’t be correct.

Be careful about how you test cases. The question asks what MUST be true. Go back to the starting point that worked for both answers: z = 0.

It’s true that, for example, 0 = (3)(0).

Does z always have to equal 0? Can you come up with a case where z does not equal 0 but the equation is still true?

Try 2 = (1)(2). In this case, z = 2 and x = 1, and the equation is true. Here’s the key to the “and” vs. “or” language. If z = 0, then the equation is always 0 = 0, but if not, then x must be 1; in that case, the equation is z = z. In other words, either x = 1 OR z = 0.

The correct answer is (E).

The above reasoning also proves why answer (A) could be true but doesn’t always have to be true. If both variables are 0, then the equation works, but other combinations are also possible, such as z = 2 and x = 1.

Key Takeaways: Test Cases on Theory Problems

(1) If you didn’t simplify the original equation, and so didn’t know that y didn’t matter, then you still could’ve tested real numbers to narrow down the answers, but it would’ve taken longer. Whenever possible, simplify the given information to make your work easier.

(2) Must Be True problems are usually theory problems. Test some real numbers to help yourself understand the theory and knock out answers. Where possible, use the answer choices to help you decide what to test.

(3) Be careful about how you test those cases! On a must be true question, some or all of the wrong answers could be true some of the time; you’ll need to figure out how to test the cases in such a way that you figure out what must be true all the time, not just what could be true.

* GMATPrep® questions courtesy of the Graduate Management Admissions Council. Usage of this question does not imply endorsement by GMAC.

Avoiding the C-Trap in Data Sufficiency

Have you heard of the C-Trap? I’m not going to tell you what it is yet. Try this problem from GMATPrep® first and see whether you can avoid it

Have you heard of the C-Trap? I’m not going to tell you what it is yet. Try this problem from GMATPrep® first and see whether you can avoid it

* “In a certain year, the difference between Mary’s and Jim’s annual salaries was twice the difference between Mary’s and Kate’s annual salaries. If Mary’s annual salary was the highest of the 3 people, what was the average (arithmetic mean) annual salary of the 3 people that year?

“(1) Jim’s annual salary was $30,000 that year.

“(2) Kate’s annual salary was $40,000 that year.”

I’m going to do something I normally never do at this point in an article: I’m going to tell you the correct answer. I’m not going to type the letter, though, so that your eye won’t inadvertently catch it while you’re still working on the problem. The correct answer is the second of the five data sufficiency answer choices.

How did you do? Did you pick that one? Or did you pick the trap answer, the third one?

Here’s where the C-Trap gets its name: on some questions, using the two statements together will be sufficient to answer the question. The trap is that using just one statement alone will also get you there—so you can’t pick answer (C), which says that neither statement alone works.

In the trickiest C-Traps, the two statements look almost the same (as they do in this problem), and the first one doesn’t work. You’re predisposed, then, to assume that the second statement, which seemingly supplies the “same” kind of information, also won’t work. Therefore, you don’t vet the second statement thoroughly enough before dismissing it—and you’ve just fallen into the trap.

How can you dig yourself out? First of all, just because two statements look similar, don’t assume that they either both work or both don’t. The test writers are really good at setting traps, so assume nothing.

Read more

How to Learn from your GMAT Problem Sets (part 2)

Recently, we talked about how to create Official Guide (OG) problem sets in order to practice for the test. I have one more component to add: track your work and analyze your results to help you prioritize your studies.

Recently, we talked about how to create Official Guide (OG) problem sets in order to practice for the test. I have one more component to add: track your work and analyze your results to help you prioritize your studies.

In the first half of this article, we talked about making problem sets from the roughly 1,500 problems that can be found in the three main OG books. These problems are generally regarded as the gold standard for GMAT study, but how do you keep track of your progress across so many different problems?

The best tool out there (okay, I’m biased) is our GMAT Navigator program, though you can also build your own tracking tool in Excel, if you prefer. I’ll talk about how to get the most out of Navigator, but I’ll also address what to include if you decide to build your own Excel tracker.

(Note: GMAT Navigator used to be called OG Archer. If you used OG Archer in the past, Navigator brings you all of that same functionality—it just has a new name.)

What is GMAT Navigator?

Navigator contains entries for every one of the problems in the OG13, Quant Supplement, and Verbal Supplement books. In fact, you can even look up problems from OG12. You can time yourself while you answer the question, input your answer, review written and video solutions, get statistics based on your performance, and more.

Everyone can access a free version of Navigator. Students in our courses or guided-self study programs have access to the full version of the program, which includes explanations for hundreds of the problems.

How Does Navigator Work?

First, have your OG books handy. The one thing the program does not contain is the full text of problems. (Copyright rules prevent this, unfortunately.)

When you sign on to Navigator, you’ll be presented with a quick tutorial showing you what’s included in the program and how to use it. Take about 10 minutes to browse through the instructions and get oriented.

When you reach the main page, your first task is to decide whether you want to be in Browse mode or Practice mode.

Practice mode is the default mode; you’ll spend most of your time in this mode. You’ll see an entry for the problem along with various tools (more on this below).

Browse mode will immediately show you the correct answer and the explanation. You might use this mode after finishing a set of questions, when you want to browse through the answers. Don’t reveal the answers and explanations before you’ve tried the problem yourself!

Here’s what you can do in Practice mode:

Read more

Save Time and Eliminate Frustration on DS: Draw It Out!

Some Data Sufficiency questions present you with scenarios: stories that could play out in various complicated ways, depending on the statements. How do you get through these with a minimum of time and fuss?

Some Data Sufficiency questions present you with scenarios: stories that could play out in various complicated ways, depending on the statements. How do you get through these with a minimum of time and fuss?

Try the below problem. (Copyright: me! I was inspired by an OG problem; I’ll tell you which one at the end.)

* “During a week-long sale at a car dealership, the most number of cars sold on any one day was 12. If at least 2 cars were sold each day, was the average daily number of cars sold during that week more than 6?

“(1) During that week, the second smallest number of cars sold on any one day was 4.

“(2) During that week, the median number of cars sold was 10.”

First, do you see why I described this as a “scenario” problem? All these different days… and some number of cars sold each day… and then they (I!) toss in average and median… and to top it all off, the problem asks for a range (more than 6). Sigh.

Okay, what do we do with this thing?

Because it’s Data Sufficiency, start by establishing the givens. Because it’s a scenario, Draw It Out.

Let’s see. The “highest” day was 12, but it doesn’t say which day of the week that was. So how can you draw this out?

Neither statement provides information about a specific day of the week, either. Rather, they provide information about the least number of sales and the median number of sales.

The use of median is interesting. How do you normally organize numbers when you’re dealing with median?

Bingo! Try organizing the number of sales from smallest to largest. Draw out 7 slots (one for each day) and add the information given in the question stem:

![]()

Now, what about that question? It asks not for the average, but whether the average number of daily sales for the week is more than 6. Does that give you any ideas for an approach to take?

Because it’s a yes/no question, you want to try to “prove” both yes and no for each statement. If you can show that a statement will give you both a yes and a no, then you know that statement is not sufficient. Try this out with statement 1

(1) During that week, the least number of cars sold on any one day was 4.

Draw out a version of the scenario that includes statement (1):

![]()

Can you find a way to make the average less than 6? Keep the first day at 2 and make the other days as small as possible:

![]()

The sum of the numbers is 34. The average is 34 / 7 = a little smaller than 5.

Can you also make the average greater than 6? Try making all the numbers as big as possible:

![]()

(Note: if you’re not sure whether the smallest day could be 4—the wording is a little weird—err on the cautious side and make it 3.)

You may be able to eyeball that and tell it will be greater than 6. If not, calculate: the sum is 67, so the average is just under 10.

Statement (1) is not sufficient because the average might be greater than or less than 6. Cross off answers (A) and (D).

Now, move to statement (2):

(2) During that week, the median number of cars sold was 10.

Again, draw out the scenario (using only the second statement this time!).

![]()

Can you make the average less than 6? Test the smallest numbers you can. The three lowest days could each be 2. Then, the next three days could each be 10.

![]()

The sum is 6 + 30 + 12 = 48. The average is 48 / 7 = just under 7, but bigger than 6. The numbers cannot be made any smaller—you have to have a minimum of 2 a day. Once you hit the median of 10 in the middle slot, you have to have something greater than or equal to the median for the remaining slots to the right.

The smallest possible average is still bigger than 6, so this statement is sufficient to answer the question. The correct answer is (B).

Oh, and the OG question is DS #121 from OG13. If you think you’ve got the concept, test yourself on the OG problem.

Key Takeaway: Draw Out Scenarios

(1) Sometimes, these scenarios are so elaborate that people are paralyzed. Pretend your boss just asked you to figure this out. What would you do? You’d just start drawing out possibilities till you figured it out.

(2) On Yes/No DS questions, try to get a Yes answer and a No answer. As soon as you do that, you can label the statement Not Sufficient and move on.

(3) After a while, you might have to go back to your boss and say, “Sorry, I can’t figure this out.” (Translation: you might have to give up and guess.) There isn’t a fantastic way to guess on this one, though I probably wouldn’t guess (E). The statements don’t look obviously helpful at first glance… which means probably at least one of them is!

My GMAT Score Dropped! Figuring Out What Went Wrong

Did you know that you can attend the first session of any of our online or in-person GMAT courses absolutely free? We’re not kidding! Check out our upcoming courses here.

I’m reviving an old article I first wrote five years ago (time flies!) because the topic is so important. I hope that no one ever again experiences a significant GMAT score drop on the real test (or even a practice one!), but the reality is that this does happen. The big question: now what? Read more

When is it Time to Guess on Quant?

So you’ve been told over and over that guessing is an important part of the GMAT. But knowing you’re supposed to guess and knowing when you’re supposed to guess are two very different things. Here are a few guidelines for how to decide when to guess.

So you’ve been told over and over that guessing is an important part of the GMAT. But knowing you’re supposed to guess and knowing when you’re supposed to guess are two very different things. Here are a few guidelines for how to decide when to guess.

But first, know that there are two kinds of guesses: random guesses and educated guesses. Both have their place on the GMAT. Random guesses are best for the questions that are so tough, that you don’t even know where to get started. Educated guesses, on the other hand, are useful when you’ve made at least some progress, but aren’t going to get all the way to an answer in time.

Here are a few different scenarios that should end in a guess.

Scenario 1: I’ve read the question twice, and I have no idea what it’s asking.

This one is pretty straightforward. Don’t worry about whether the question is objectively easy or difficult. If it’s too hard for you, it’s not worth doing. In fact, it’s so not worth doing that it’s not even worth your time narrowing down answer choices to make an educated guess. In fact, if it’s that difficult, it may even be better for you to get it wrong!

To make the most of your random guesses, you should use the same answer choice every time. The difference is slight, but it does up your odds of getting some of these random guess right.

Scenario 2: I had a plan, but I hit a wall.

Often, when this happens, you haven’t yet spent 2 minutes on the problem. So why guess? Maybe now you have a better plan for how to get to the answer. I know this is hard to hear, but don’t do it! To stay on pace for the entire section, you have to stay disciplined and that means that you only have one chance to get each question right.

The good news is that no 1 question you get wrong will kill your score. But, 1 question can really hurt your score if you spend too long on it! Once you realize that your plan didn’t work, it’s time to make an educated guess. You’ve already spent more than a minute on this question (hopefully not more than 2!), and you probably have some sense of which answers are more likely to be right. Take another 15 seconds (no more!) and make your best educated guess.

Scenario 3: I got an answer, but it doesn’t match any of the answer choices.

This is another painful one, but it’s an almost identical situation to Scenario 2. It means you either made a calculation error somewhere along the way, or you set the problem up incorrectly to begin with. In an untimed setting, both of these problems would have the same solution: go back over your work and find the mistake. On the GMAT, however, that process is too time-consuming. Plus, even once you find your mistake, you still have to redo all the work!

Once again, though it might hurt, it’s still in your best interest to let the question go. If you can narrow down the answer choices, great (though don’t spend longer than 15 or 20 seconds doing so). If not, don’t worry about it. Just make a random guess and vow to be more careful on the next one (and all the rest after that!).

Scenario 4: I checked my pacing chart and I’m more than 2 minutes behind.

Pacing problems are best dealt with early. If you’re more than 2 minutes behind, don’t wait until another 5 questions have passed and you realize you’re 5 minutes behind. At this point, you want to find a question in the next 5 that you can guess randomly on. The quicker you can identify a good candidate to skip, the more time you can make up.

This is another scenario where random guessing is best. Educated guessing takes time, and we’re trying to save as much time as possible. Look for questions that take a long time to read, or that deal with topics you’re not as strong in, but most importantly, just make the decision and pick up the time.

Wrap Up

Remember, this test is not like high school exams; it’s not designed to have every question answered. This test is about consistency on questions you know how to do. Knowing when to get out of a question is one of the most fundamental parts of a good score. The better you are at limiting time spent on really difficult questions, the more time you have to answer questions you know how to do.

Plan on taking the GMAT soon? We have the world’s best GMAT prep programs starting all the time. And, be sure to find us on Facebook and Google+, and follow us on Twitter!

Manhattan Prep’s Social Venture Scholars Program Deadline: March 28

Do you promote positive social change? Do you work for a non-profit? Manhattan Prep is offering special full tuition scholarships for up to 16 individuals per year (4 per quarter) who will be selected as part of Manhattan GMAT’s Social Venture Scholars program. SVS program provides selected scholars with free admission into one of Manhattan GMAT’s live online Complete Courses (a $1290 value).

Do you promote positive social change? Do you work for a non-profit? Manhattan Prep is offering special full tuition scholarships for up to 16 individuals per year (4 per quarter) who will be selected as part of Manhattan GMAT’s Social Venture Scholars program. SVS program provides selected scholars with free admission into one of Manhattan GMAT’s live online Complete Courses (a $1290 value).

These competitive scholarships are offered to individuals who (1) currently work full-time in an organization that promotes positive social change, (2) plan to use their MBA to work in a public, not-for-profit, or other venture with a social-change oriented mission, and (3) demonstrate clear financial need. The Social Venture Scholars will all enroll in a special online preparation course taught by two of Manhattan GMAT’s expert instructors within one year of winning the scholarship.

The deadline is fast approaching: March 28, 2014!

Learn more bout the SVS program and apply to be one of our Social Venture Scholars here.

Ron Purewal’s Upcoming Live Online GMAT Course Available at Special International Time

Manhattan GMAT’s Live Online Spring P2 Course is a comprehensive GMAT course designed specifically for high-achieving, international students looking to earn an MBA from a top business school. Taught by famed GMAT instructor, Ron Purewal, our Live Online Spring P2 Course will be hosted in the early morning (5:30AM-8:30AM PDT) from Silicon Valley, California.

We’re inviting students from all around the world to join, with the hope that this unique time will fit more conveniently into international students’ schedules. The course aims to teach mastery of GMAT content and the test-taking skills and strategies that are necessary to conquering every question type with confidence.

The Live Online Spring P2 Course with Ron Purewal begins April 16th, 2014 and includes:

• 54 hours of class time & coaching – at a time specifically selected to best support international GMAT test-takers.

• Strategy Guides that equip you for the entire GMAT: math and verbal theory, problem solving techniques, essential formulae, and hundreds of examples

• Every Official Guide for GMAT Review (that’s over 1400 real GMAT problems!)

• Foundational math and verbal primers—including books, question banks, and online workshops to help you review

• Full Integrated Reasoning training, plus an online bank of questions for additional practice

• Six full-length Computer Adaptive Practice Tests, designed in-house by our veteran instructors to simulate the GMAT’s uniquely adaptive format

• Detailed practice dashboards that show you how you’re performing (including stats on accuracy, speed, and difficulty level) across every specialized math and verbal topic

• On Demand Class Recordings so you can review course concepts anytime

• eBook downloads of every Manhattan GMAT Strategy Guide, accessible on your iPad, Nook, smartphone, or other compatible mobile device

• Challenge problems, interactive labs, essay grading software, and dozens of additional resources

Space is limited and filling quickly, so be sure to register for Ron Purewal’s upcoming Live Online GMAT Course at this special international time before it’s too late.

Not sure if this class is right for you? Attend the first session for free and try it out before signing up for the complete program.